Nearly three decades and 12 studio albums into Opeth’s career, Mikael Åkerfeldt alighted at the end of the Sorceress tour cycle in the autumn of 2018 feeling more than ready for a lengthy break and some much needed rest and recuperation in the company of his family. With no urgent need to write new music, it was time to put his moccasins up and enjoy some downtime. Piecing together another elaborate, all-consuming Opeth album could wait until much further down the line. Christmas was coming. Chill out, Åkerfeldt, just for once.

“But yeah, I guess I couldn’t stop myself,” he grins, as Prog chats with the Opeth frontman in celebration of In Cauda Venenum , the band’s 13th musical observation and an album that seemingly took its creator by surprise.

“We came home in late November and I knew we had December off, with Christmas coming up, and I wanted to be with my kids and my girlfriend and not do anything. I wanted to get away from the band, which you do, especially if you’re so closely connected to it. But obviously my girlfriend and kids aren’t at home all the time. They’re at school or work or studying, so I’m at home just sitting. That was never a problem for me when I was younger, to spend time with my record collection and just sit around, but now I can’t do that anymore because I feel useless.”

There has always been something about Opeth’s music that makes it easy to forget the human being behind those extraordinary, otherworldly explorations. You might imagine that someone with Åkerfeldt’s talent would always feel assured of his place and purpose in the world, but he freely admits to have endured a brief but telling moment of self-doubt.

“I think that’s something to do with having gone through a divorce, actually, because I want to redeem myself,” he notes with a wry smile. “Not just to the people who were affected by that but also to me. I feel I’m there now and I’m happy, but what’s changed is that I’m more restless than I was. So when the kids are at school or studying and my girlfriend’s at work, I’m a useless twat, sitting around and waiting for them to come home, like a dog pretty much. So I had to do something…”

Anxious to occupy his time, Åkerfeldt took the logical step of heading down to Opeth’s studio to give it all the equipment a routine check, just to make sure that everything was in working order for whenever he finally decided to start work on the next album. Creativity isn’t a tap that can be turned on and off at will, of course, but it will surprise no one that within hours of entering the studio, Åkerfeldt’s artistic engine was flickering into life.

“I think I wrote the opening part to Svekets Prins [English title: Dignity] that day,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘That’s not bad, actually!’ and off I went. I started writing. I was there all the time when my girlfriend and kids weren’t at home. I took my kids to school, my girlfriend’s off studying, and I was there at the studio from eight in the morning, working. It felt good, to be occupied and not feel useless. At the time I didn’t know if it was going to amount to a record or if I was just playing around. It’s like playing with Lego, making music. You can put the pieces together in different ways. There isn’t a set way to play with Lego and you can create something out of your own imagination. That’s where this record came from.”

(Image credit: Atomic Fire Records)

There are two things that every Prog reader needs to know about In Cauda Venenum . Firstly, it’s almost absurdly brilliant. Secondly, its songs are sung entirely in Swedish. As observant Opeth fans will already have noted, In Cauda Venenum will be available in English, too, but Åkerfeldt makes a point of stating that he regards the Swedish version as the “real” version of the album. Not that there was any huge agenda behind his decision to write in his first language. As he explains it, the process of writing a new Opeth album has routinely been aided by some overarching idea or concept that, initially at least, helps to guide the frontman through fresh compositional territory. For 2002’s Deliverance and 2003’s Damnation , the task was to create one super-heavy album and one soft and mellifluous one. For 2008’s Watershed , he focused on unsettling wrongness, inspired by a love of Scott Walker’s avant-garde phase. This time around, the decision to write in Swedish appears to have been inspired by little more than curiosity, but the end result is an album that Åkerfeldt admits is the most direct and personal that Opeth have made.

“As you know, my English lyrics are embellished with words that English people haven’t seen since the 1800s,” he deadpans. “I love the English language, but it’s also a case of me not considering myself a great lyric writer. I hide behind English and create amateurish, childish poetry with all these beautiful words. Our fans get annoyed when I say this because to them it’s not shit, the lyrics have substance to them. I’m not saying that everything I’ve written is shit, but there are degrees of quality! [Laughs] But this time I couldn’t hide behind anything. We don’t have any beautiful words in Swedish. So I wrote the lyrics without that security or that safety net of beautiful words and the lyrics came out modern, contemporary and semi-political in parts. I’ve never done that before. That was fucking fun, I have to say. There’s more substance to them as a result of that.”

This is not the first time that Åkerfeldt has sung in Swedish. Opeth recorded a cover of Den Ständiga Resan by Marie Fredriksson (yes, the one from Roxette) that appears on the special edition of Watershed , and the singer remembers receiving a lot of positive feedback and even the occasional suggestion that he should do more of the same. Having embraced the idea of writing a full album in his native tongue, he swiftly came to the conclusion that one major creative risk was probably enough and that In Cauda Venenum needed to be, in every other conceivable respect, a triumph.

“The thing is, the music doesn’t sound any more Swedish than before!” Åkerfeldt chuckles. “But one thing I made sure of was that I didn’t let anything slide. I couldn’t have a single second on there that I would have any doubts about. I just wanted everything exactly as I wanted. That was important to me, to do a record in my own language and not have any part of it be half-assed. It’s going to leave my hands, firstly into the hands of the band and then to the engineer and the managers and soon enough everything else takes over. But I had my back covered and that was important.”

There’s a pleasing duality to In Cauda Venenum ’s linguistic detour. On the one hand, hearing Mikael Åkerfeldt singing in Swedish gives the record’s already immersive songs an extra layer of enigmatic charm. On the other, composing in his own language had a fundamental impact on the kind of lyrics that he was writing. Don’t expect the album to be full of political polemic or furious diatribes about the state of the world in 2019… oh, actually, maybe you can expect a bit of that.

“Yeah, it is more political, more personal, too. But not so much personal for me or my persona as an artist. It’s more personal in terms of being Swedish,” he shrugs. “It’s what black metal bands used to call ‘society lyrics’ – they used to hate that! [Laughs] But that’s what it is, basically. It has more of an affinity with [ultra-noisy/political extreme metal pioneers] Napalm Death’s Scum album than with Edgar Allan Poe. But I still wanted to have that aesthetic thing, too.”

It would be a stretch to say that In Cauda Venenum (translation: “poison in the tail”) is a political record, and Roger Waters has nothing to worry about on that score, but there are numerous little touches that set the album apart from its predecessors, not least the persistent use of voiceovers and recorded dialogue. This is particularly effective on Svekets Prins , the album’s opening track proper (following the trippy, Tangerine dreamscape of intro Livet’s Trädgård ), which features a speech by former Swedish prime minister Olof Palme.

“He was murdered in 1986, shot in the street, and it’s still unsolved,” Åkerfeldt notes. “There are lots of conspiracy theories surrounding that murder. He was a social democrat which, yeah, I am too. And he was a political icon. He was controversial. In a small little country like Sweden he stood up against the US. So he was iconic but a lot of people hated him, which is why he got killed. I’m very happy we got permission to have him on the record.”

In addition to the revelation that he is becoming a bit angrier in his old age, Åkerfeldt also discovered that singing in Swedish revealed another interesting detail about his abilities as a vocalist.

“Yeah, I was presented with my speech impediment for the first time,” he says, shaking his head in mock exasperation. “I can’t roll my R’s. You wouldn’t know that because English people don’t generally go around rolling their Rs, unless you’re Vincent Price or Christopher Lee. Overseas, no one has ever said, ‘Oh, you sound stupid!’ But I instantly became aware, the more I did it in the studio. I could tell it sounded a bit iffy. So I asked my friend Jonas [Renkse, Katatonia vocalist] whether I should just try to pretend I’m a classical actor on the stage or something, but he said, ‘No, you’re golden! You just have the Stockholm ‘R’. It’s vintage. It’s the way we used to speak in the city before the internet!’ So basically it’s like David Coverdale going back to his broad Yorkshire accent! It’s just how I speak and it’s a bit slurry, but that’s how we older cunts sound in Sweden, okay?”

(Image credit: Jonas Akerlund)

One thing that has characterised Mikael Åkerfeldt’s creative journey over the last 30 years has been a haughty but healthy disregard for what the fans may be expecting or demanding from his band. As a result, there is something slightly jarring about the decision to release an English version of In Cauda Venenum . Releasing an album with lyrics that the majority of fans can’t understand seems like a fairly Opeth thing to do, all told. Releasing an English version seems a bit like a compromise, which isn’t a very Opeth thing to do at all.

“Well, the plan originally was not to make an English version,” he sighs. “But yeah, I was insecure about the whole thing. Not in terms of sales. Don’t get me wrong, I like money, but that wasn’t the point. The fact is, I love this album and if there was any barrier between people picking this up or not, I didn’t want it. If you’re a fan, maybe not understanding what I’m singing about could be a problem. Because it’s been a problem for me, with the whole Italian prog scene, for example. It took me a while to get into that. There was a time when I wasn’t interested if I couldn’t understand what was being said. So I figured that if there are any other people out there who feel the same way, at least there’s a version for them. But yeah, it was an insecurity issue, basically.”

How have people reacted to the Swedish version so far?

“Most people, when I played it to them, didn’t even acknowledge that I was singing in Swedish until halfway through the second song,” he smiles. “Like, ‘Oh, is it Swedish?’ [Laughs] So that’s nice, that there isn’t that much of a difference. Most people who don’t speak English that I’ve played it to have said, ‘So why the English version?’ as opposed to ‘Why the Swedish version?’ That’s interesting, I think. People are more open-minded than I thought. So far, anyway!”

Having decided to record in two different languages, Åkerfeldt was faced with the task of translating his Swedish lyrics into English. As he noted earlier, Swedish and English are fundamentally different in many ways, so was it possible to translate the songs accurately?

“In the end I used poetic freedom,” he smiles. “That basically means a lot of grammar errors. They could be in there but somebody can point out something that’s wrong and I’ll just say, ‘I’m a poet! I’m an artiste, so fuck you!’ But no, it was fairly easy, actually. Most of it I could translate straight off. There were some things I couldn’t translate, so the lines in English are different, but they deal with the same things. You will end up at the same place, either way. If you didn’t it’s because I’m dumb and I can’t get my point across!”

While Åkerfeldt makes a point of stating that writing lyrics in Swedish has had no discernible effect on Opeth’s music, the songs on In Cauda Venenum are anything but predictable. We may be somewhat spoiled as Opeth fans, but even by their usual standards, the depth of imagination on display during the likes of new epics Hjärtat Vet Vad Handen Gör (Heart In Hand) and Ingen Sanning Är Allas (Universal Truth) is frequently breathtaking. As Åkerfeldt states with obvious pride, it’s a big, bombastic, overblown, indulgent and often wilfully weird record that absolutely reeks of lofty artistic ambition.

“I wanted to make a masterpiece, to be honest,” he grins. “My girlfriend and I have wine evenings where we listen to records. We come up with a theme for the evening, so you can only listen to Southern rock or music from 1966 or male singers or bands from a particular country. The theme for one evening was masterpieces, but that presented a problem to me because many of my favourite bands don’t have songs that would meet that criteria. I couldn’t play any KISS songs. I couldn’t play any Deep Purple songs. I could play one Rainbow song, Stargazer , and I wanted to get Tarot Woman in there, but [my girlfriend] Clara said no. It doesn’t make me cry and that should be the criteria. It should make you feel something beyond music, something that makes you think of your childhood or a previous girlfriend or a shit time or a good time in your life. That was the type of music that I wanted to write for this record.”

And does he think he’s succeeded? Is this Opeth’s masterpiece?

“Well, the irony is that it’s impossible for me to say whether I succeeded or not, because I’m not sitting around crying to my own music. But I wanted to increase the potential for the listener by having those natural attributes of masterpieces that make people cry. It’s that big, overblown, pompous stuff that I love anyway, so it wasn’t a stretch. I ended up with what I think is a beautiful record. Of course

In Cauda Venenum ’s masterpiece credentials will doubtless be debated for the foreseeable future, but there’s no disputing how wonderfully rich and detailed the new Opeth material is. Both Sorceress (2016) and Pale Communion (2014) were recorded at the legendary Rockfield Studios in Wales, but Åkerfeldt is not a man inclined to repeat himself too much. For the new album, Opeth stayed in Stockholm, recording at Park Studios, which can be found “where the areas Örby, Älvsjö and Liseberg meet” (according to the studio’s website). If Rockfield had been an easy choice, not least based on its remarkable history, Park was a more low-key option that only occurred to Åkerfeldt after a dinner date with a fellow rock star.

“I’ve been aware of that studio since forever but I’d forgotten about it until I had dinner with Tobias [Forge] from Ghost,” he recalls. “He said ‘It’ll be right up your alley!’ and he was right. It’s a really nice, cosy studio. Rockfield was an obvious choice. I wanted to be there 10 or 15 years ago but I figured it was out of our price range, basically because Oasis had been there! [Laughs] It turns out that it’s fucking cheap by standards in Sweden, for instance. Park is quite expensive, actually. But it’s co-owned by a Swedish pop band called Kent. They’re massive in Scandinavia. They’ve split up now but the guitarist still co-owns the studio with Stefan [Boman] who engineered our record. It’s right next door to where my mother used to live so I knew it was there but I guess I needed Tobias to remind me.”

Given Opeth’s penchant for the warm tones of classic progressive rock and other arcane sonic styles, and their hard-to-deny identity as avid studio nerds, a cynic might expect that Mikael Åkerfeldt spends an inordinate amount of studio time sourcing cobweb-encrusted bits of ageing kit to make sure that none of that nasty digital technology interferes with the authenticity of the whole thing. But despite his refined creative instincts, he remains thoroughly laidback about the relative merits of analogue and digital recording. One way or another, Park Studios seems to have ticked every possible box.

“I don’t really care what it is we use, to be honest. If it’s a synthetic plug-in or a real device from the 60s, it doesn’t matter,” he notes, cheerily. “As long as it sounds good,

(Image credit: Jonas Akerlund)

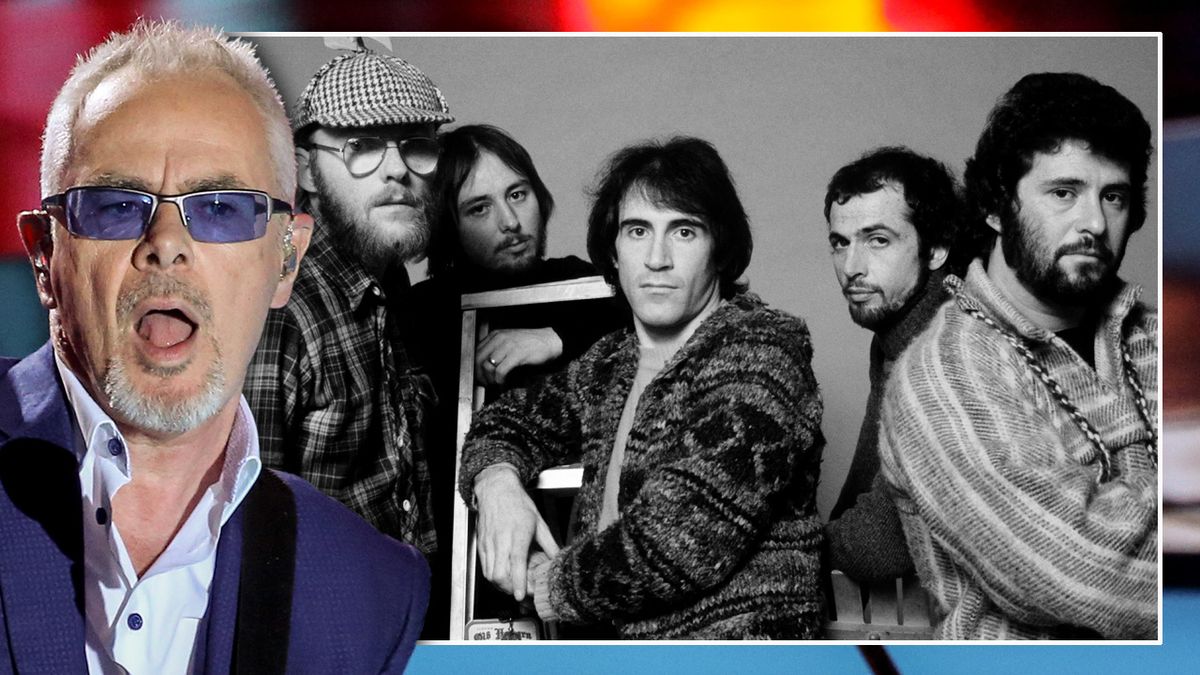

A few recalcitrant Blackwater Park -worshipping diehards aside, the majority of Opeth fans must surely have acknowledged the sublime chemistry between the band’s current line-up. With keyboard maestro Joakim Svalberg proving to be the final piece in the personnel puzzle, Opeth have visibly and audibly grown in strength as a live band in recent years, gaining more momentum as a band in the process. Fittingly, In Cauda Venenum is full of dazzling ensemble performances, from the juddering prog metal groove-a-thon of Charlatan (the album’s only song that has a title that works in both Swedish and English, language fans!) to the stirring slow-burn of closing epic Allting Tar Slut (All Things Will Pass). But it’s also an album embellished with some gloriously intricate string arrangements, particularly on its most bewildering track, De Närmast Sörjande (Next Of Kin). Orchestrated by Egg/Hatfield And The North legend Dave Stewart (who previously worked with Opeth on 2014’s Pale Communion ), it’s a grandiose but deliciously perverse piece of music with echoes of late-60s raga rock freak-outs and Indian classical music.

“Yeah that’s one of my favourites. It’s one of the hardest ones to get into, but when people do get into it, it seems to be a favourite,” says Åkerfeldt. “I think it sounds like it’s from a West End musical. I don’t know where that came from, to be honest. I have no idea. I can’t point to a direct influence on that song. The first working title was ‘Floyd’. I wanted it to sound like Astronomy Domine , all twangy, but then I ended up with that. To use an old cliché, that song wrote itself. It’s a complex piece of work, but done in a day.”

Ever the student of prog rock history, Åkerfeldt eagerly notes his delight at working with Dave Stewart again.

“Unfortunately I wasn’t there for that session, but Dave is amazing. I love Egg and National Health and all of that, and he played on the Arzachel album [1969 psychedelic classic, also featuring guitar legend Steve Hillage], which is one of my favourites. Last time, we asked him about how he got the organ sound for Arzachel, he said, ‘Oh it’s a horrible sound, too much reverb… but here we go!’ and he had it all ready! He lives out in the sticks somewhere and doesn’t have an internet connection… or he does but it’s so bad that he can’t send files over the internet. He doesn’t have a cellphone either, so I called him up and Barbara Gaskin answers… my idol! [Laughs] I wanted to go, ‘I love you Barbara!’ … but I didn’t. Oh well.”

Even in such a great year for albums, In Cauda Venenum stands out as a fearsome demonstration of musical prowess, albeit from a band that have made a habit of such things. More importantly, the 13th Opeth album is very pointedly designed to be listened to in full, and preferably on vinyl, as the band’s ongoing resistance to the instant gratification and short attention spans of the streaming era is presented in its most lavish and substantial form yet. Åkerfeldt joyously notes that 2016’s Sorceress became Nuclear Blast Records’ best-selling vinyl record ever upon its release in 2016, and while Opeth have never shied away from making their music available on streaming platforms, he remains a passionate advocate for the dying art of truly listening to music and respecting its life-affirming power. They might not be taking to the streets with Molotov cocktails quite yet, but Opeth’s stoic resistance to the throwaway continues.

“It’s reassuring that people really listen to our music. I’m hoping that’s true. I think it is. I guess that’s why we’re not the biggest band on streaming platforms. I do have Spotify, for instance. I was forced to get a family account for my kids, and yeah it’s fucking convenient, but shit, you listen to music in a completely different way, with no respect. Even me, sitting on a subway, I could miss a potential masterpiece because the format makes me restless. It’s the respect for music that seems to be lost a little bit, I think. I’m sure Prog readers love music and they’ll give this record the time it deserves. And yes, we are part of the resistance. That’s exactly how it is.”

![Carla Harvey [Ex-Butcher Babies] Joins Classic ’90s Band Carla Harvey [Ex-Butcher Babies] Joins Classic ’90s Band](https://townsquare.media/site/366/files/2025/01/attachment-carla-harvey-2025.jpg?w=1200&q=75&format=natural)

#vevo #shots #youtube #vevoofficial

#vevo #shots #youtube #vevoofficial