London punk band The Clash is perhaps best remembered (the band hadn’t really been active since the original breakup in January 1986, and not at all since original member Joe Strummer died in 2002) for its platinum-selling London Calling, a pivotal release in British rock n’ roll revival. The band’s brief career of just under a decade had its other moments, though, not least the sometimes unheralded song Bankrobber.

Poorer Classes

Robbery is one of humanity’s oldest genres, arguably dating back to the Old West but large sums of wealth have always attracted sticky fingers. The idea is still alive in movies like Heat (1995), The Italian Job (1969), and even Die Hard: With a Vengeance (1995) but casinos – so often the target of heists in Hollywood – have their take on the concept too. The 333 Boom Banks slot from Games Global tasks the player with sneaking past security and cracking open a safe. This classic 5×3 game includes imagery of cash and bullion on the reels, as well as three colored safes that can be opened.

Ironically, for a band accustomed to lyrics about poverty, hardship, climate change, government, and many other things that bother the poorer classes the most, The Clash’s 1980 single Bankrobber seems like a look at what Hollywood presents as a high-life, huge payouts from a “last, big job” lining the pockets of those who don’t need it. Bankrobber has a realistic bent. Strummer and Mick Jones’ lyrics speak of theft as work. “But I don’t believe in lying back / Sayin’ how bad your luck is.”

“David Bowie Backwards”

Bankrobber tells a familiar The Clash story of a down-on-his-luck character. The heist is an act of desperation yet one the protagonist finds agreeable. “He just loved to live that way / And he loved to steal your money.” Far Out Magazine claims the song was “taken literally by many”, something that NME claimed, in 1991, reached a logical extreme when two actors in the Bankrobber music video were questioned by real-life police.

On their website, The Clash describes their record company’s reluctance to release Bankrobber, which never appeared on any album until the 1980 compilation Black Market Clash. This record also included Capital Radio One, Time is Tight, and Pressure Drop. Execs complained that Bankrobber sounded like “David Bowie backwards”. Oddly enough, its success in the Dutch singles chart ensured that it received radio play six months later.

“Washed Up”

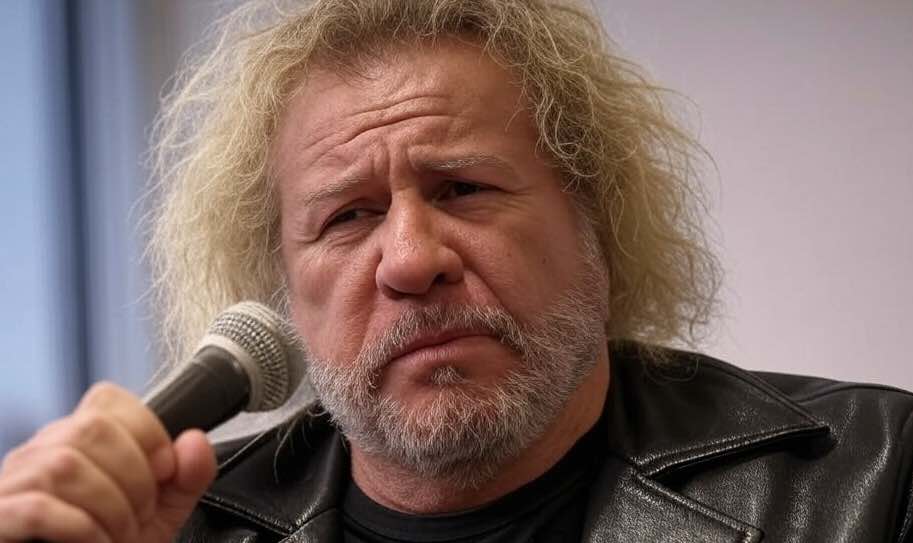

Mick Jones has his own version of Bankrobber’s story. The guitarist hinted that his father could have been a bank robber’s “assistant”, noting that he worked as a taxi driver. The whole idea might seem ridiculous today, in the high-tech banking world, where everything exists as numbers on a screen. Back then, the single was written “so everybody could relate to it” – perhaps not so much the heist itself but the joy of finding a quick fix for poverty or working your way out of a perilous life.

In 1980, The Clash experienced a rapid change in fortunes. The success of London Calling (1979) ended a period road manager Johnny Green described as “washed up” in a 2019 interview with the BBC. The group famously entered the rehearsal sessions for London Calling with no new material. Bankrobber was eventually recorded with reggae artist Mikey Dread, whose services were retained for The Clash’s follow-up album Sandinista! Bankrobber is ska-tinged throughout its 4:34 run-time.

I Fought the Law

It’s perhaps fair to say that Bankrobber is one of the band’s lesser known hits, behind Should I Stay or Should I Go, Rock the Casbah, London Calling, and a cover of The Crickets’ I Fought the Law. Yet it has made an unlikely dent in pop culture, despite being written off by The Clash’s label. It’s an almost joyful song of refusal: “A lifetime serving one machine / Is ten times worse than prison.”