The purpose of this ‘zine is not to get anyone to shave their head and put on orange sheets. I’m not out to convert people to “my religion.” This ‘zine is just a humble attempt to convey some truth that I have learned in my studies and practice of Krishna Consciousness…

There are very few movements in the history of popular music that have been as legitimately rebellious and lacking an obvious commodifi-ability as straight-edge hardcore and Krishnacore. In this way, the youth crew of the late 80s and temple-based “Eastern”-oriented bands of the nineties are paradoxically kindred spirits to the contemporaneous black and death metal scenes that rode parallel, if oppositional, tracks: If you wanted to contrive and pander your way to a successful “career” in music thirty years ago, no A&R guy would’ve said, “Hey, the sure thing right now is to embrace either low-fi tremolo-picked Satanism or sell all your worldly possessions and become a Hare Krishna on an ashram?”

There is, in other words, a purity to outré art that triumphs…to the success of the un-contrivable.

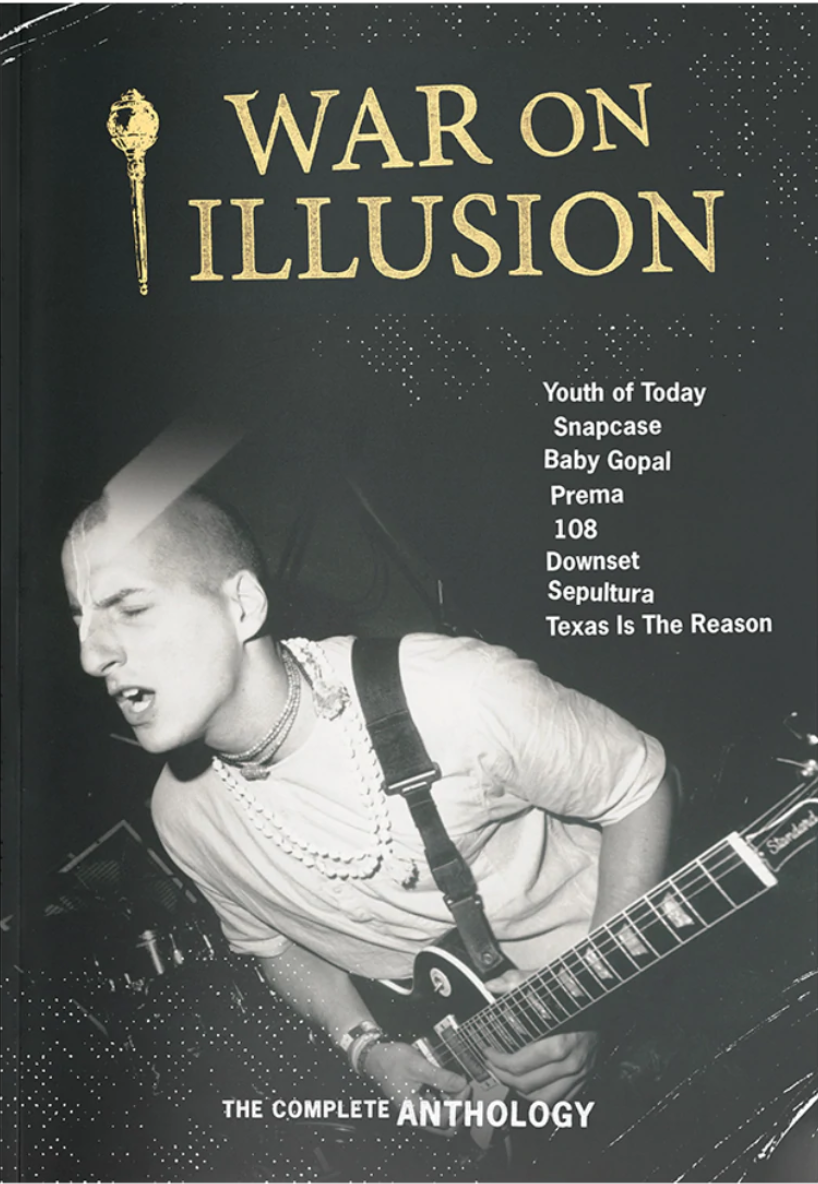

In this way, the recent collected reissue of early 90s zine War on Illusion by legendary Youth of Today/Judge/Shelter guitarist Porcell is a fascinating document not only of a bustling, molting, evolving hardcore scene, but also a blueprint for how self inventory/reflection can open the door to other modes of thinking, existence, and ethics — a proposition that has only become more urgent (and arguably necessary) in the intervening thirty years.

In addition to some pretty heady philosophical discourses — article titles here include “Stretched on the Rack of this World,” “Anarchy, Mohawks, and the Existence of Freedom,” “Not this Body,” “City Gardens, Chain Wallets, and the Existence of God” — and Ray Cappo’s YoT tour diaries, Porcell proves himself a deft and incisive interviewer in these pages, frequently questioning his own premises and empathetically nudging subjects into deeper conversations.

He walks, for example, a circa Do We Speak a Dead Language? Rey from Downset through a growing ambivalence about feuds with Zack from Rage Against the Machine and the message of the band’s signature song, “Anger.” (“That song was written at a dark time in my life and sometimes I worry that I’m influencing kids in a dark way. I hope it doesn’t fuel their lower nature. I would never want to say anything or do anything that’s going to hurt anyone or degrade anyone. That part of my life is over. But, man, people like that song. I don’t know what to do.”) Or when he asks Igor Cavalera to define suffering. (“Loneliness is the worst kind.”) Or Vic DiCara talking about getting pulled over while on tour with 108 in full robe regalia by some good old boy cops in Texas who snicker at his “dress” until he tells them he’s a priest — and gives a short sermon to boot. (“I explained to [the sheriff] the four regulative principles, that we don’t take any intoxication, we don’t eat meat, we don’t gamble, and we don’t have illicit sex. And he goes, ‘You d mean to say you don’t have illicit connections with women? You’re a better man than I am, son!’ Then he turns to the other cops and says, ‘They’re all priests! Let ’em go!’”) Or Daryl from Snapcase doing a track by track on Lookinglasself. (“I mean, confrontation is good. There’s nothing wrong with confrontation. But the thing that bothers me is the methods that people choose to confront each other with.”)

“I’ve always been one of those guys that’s on a mission,” Porcell says in an opening retrospective interview. “I like to live my life for a greater purpose, you know what I mean? Whenever I found something in my life that had great value to me, I felt compelled to share it with other people. I’m a naturally enthusiastic person, I think. If it has helped me. then it might be able to help somebody else, so why not shout it from the rooftops?”

And so he did — and it continues to echo today.

![DEAR X [EP 4] Love Story 💕💕💕💞💞 #clamvevo #kiparabrand #dontatv #love #movie #comedy DEAR X [EP 4] Love Story 💕💕💕💞💞 #clamvevo #kiparabrand #dontatv #love #movie #comedy](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/ACCH9SwXu84/maxresdefault.jpg)