Few sounds summon the American frontier as instantly as that lone ocarina cry in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly — “ah-ee-ah-ee-ah,” as it’s lovingly remembered. Yet its mastermind, Italian legend Ennio Morricone, who passed away at 91 in Rome, didn’t set foot in the United States until 2007. That’s more than four decades after composing the score that would come to influence various music genres, including our beloved pop sounds.

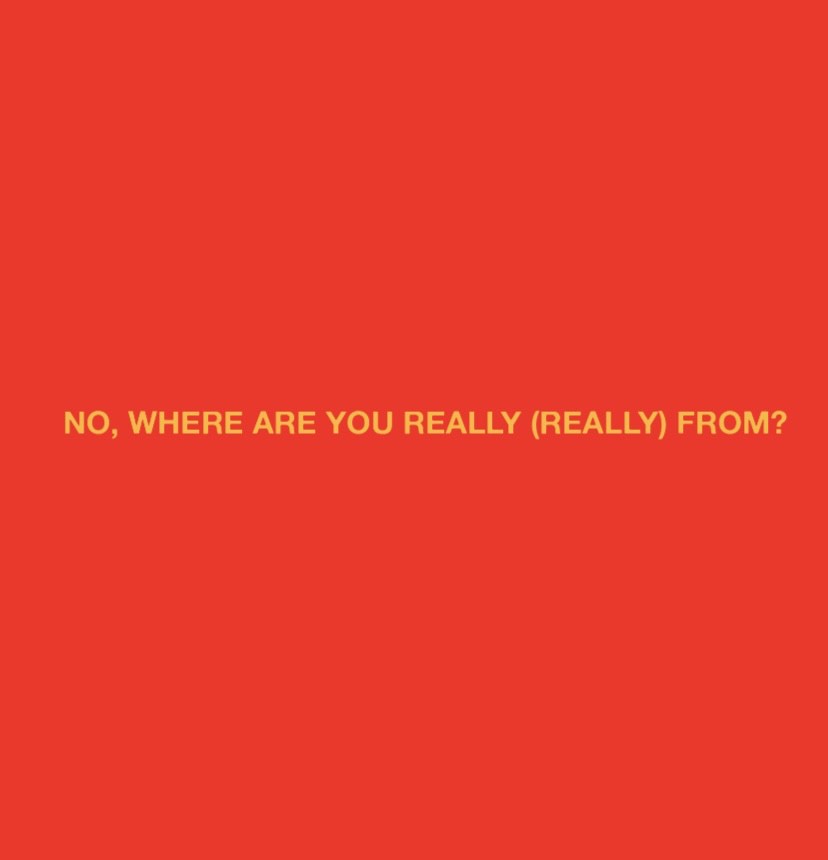

But how did a man who never mastered English or wandered through Monument Valley’s red rock buttes or Arizona’s dusty outposts so perfectly channel the lonely, rugged heart of the Southwest?

Over the years, Morricone didn’t merely accompany Western filmmakers’ visions; he upended them, carving out a raw, unvarnished soundscape that replaced sweeping orchestral flourishes with what he later described as ‘the music of reality.’

Morricone’s legacy extends much further than the blowing dust and rolling tumbleweeds in his famous Western film scores.

Over a career that totaled around 500 film soundtracks, he moved effortlessly from Sergio Leone’s iconic ‘Spaghetti Westerns’ to Gillo Pontecorvo’s searing political drama ’The Battle of Algiers’ (1966), and from the eerie tension of Dario Argento’s ‘The Bird with the Crystal Plumage’ (1970) to the oceanic thrills of Michael Anderson’s ‘Orca’ (1977). He even contributed the haunting strains in Terrence Malick’s pastoral epic ‘Days of Heaven’ (1978) and Quentin Tarantino’s snowy chamber piece ‘The Hateful Eight’ (2015).

Yet, despite his astonishing range, Morricone grew weary of being forever linked to the ‘Man with No Name’ films. In a cheeky 2006 interview with The Guardian, he quipped that ‘A Fistful of Dollars,’ Clint Eastwood’s screen debut as the laconic antihero, was “the worst movie Leone made and the worst score I ever wrote.”

It’s easy to get tangled in the “chicken or egg” question with Morricone’s Western themes. Do we instantly hear the American frontier because his music shaped our idea of it? After all, those whistled melodies and staccato guitars have been quoted and spoofed so often that even a Leone novice can pick them out.

Plus, the fact that Morricone’s reach goes far beyond film boosts this case. ‘Hell Yes’ by Beck lifts those notoriously popular haunting motifs while ‘Civil War,’ by Guns N’ Roses’ features Morricone’s sparse, echoing guitar lines, known for channeling a tensely charged vibe.

And it doesn’t stop at music. Online casino game studios have also tapped into Morricone’s Wild West soundscapes.

Play’n Go, for instance, sprinkles Morricone-style whistles and guitar licks into Sticky Bandits, while Microgaming leans on eerie harmonica swells for Wild Wild West: The Great Train Heist. Even in the best casino sites, those lonely desert notes still cut through, proof that Morricone’s dusty, suspenseful magic is as potent today as it was in film.

But again, we could be familiar with Morricone’s sounds just because the Rome-based composer simply tapped into a truer Wild West than his Hollywood peers ever imagined. One not glorified by sweeping strings, but haunted by its own shadowed past.

What we do know is that Morricone broke away from the typical Western scoring style that treated the frontier like a 19th-century Romantic tableau. That is music that glorifies the lone cowboy’s march into lawless territory. Think more Frontierland pageantry than the gritty, untamed reality of the actual frontier.

Instead, Morricone opted for a darker take on the frontier. He dug into its unique soundscape and used his instruments to echo the region’s natural noises, thus painting vivid, almost cinematic scenes through music. In The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, for example, he famously replicated a coyote’s call “Aie-aye-aaah,” making that lonely howl the film’s central motif.

Today, it’s rather impossible to draw the western genre from Morricone’s sounds. Despite creating these genius works of art being 5,500 miles away from the place he acoustically describes in his film score, there is no denying that he has greatly influenced and reshaped our entire pop-culture soundtrack.

As a matter of fact, it’s virtually impossible to hear a lone whistle or sparse guitar twang without thinking of Morricone’s dusty vistas — and filmmakers, game designers, and ad execs know it.