Jonathan Weiner never set out to be a professional photographer. Picking up a camera for the first time as a teenager was, initially, simply a way to hang out with his friends and, crucially, get the best view possible not afforded to those onstage at the gigs he was frequenting as many as five times a week. The fact it gave the otherwise directionless young kid something to do, well, that was a bonus, too.

Fifteen or so years on, Weiner is one of the scene’s premier documentarians, shooting iconic images, album sleeves and magazine covers for artists and publications the world over. Even if you don’t know his name, you’ll know his work — no doubt you’ve bought any number of copies of Alternative Press bearing his photos.

Read more: 20 greatest punk-rock guitarists of all time

Talking about himself does not come easily to Weiner, as humble a person as he is infinitely talented. Getting him to reflect on approaching two decades of work isn’t the easiest of tasks, either, due to his perpetual forward motion. “I tend to just put things in a box and walk away from them,” he says, with no degree of negativity, of his work. “It’s fun to look back sometimes because I’ll see things where I may not have been as excited about them before. But I don’t do it as often as I probably could. Whenever somebody asks me, ‘What’s your most pinch-yourself moment?,’ I hope I have a new answer every year, as things just get crazier. When someone says, ‘What’s the best thing you’ve ever shot?,’ well, to be able to answer that feels wrong to me. Hopefully, I’m always moving forward, and I’m always improving.”

Before you were a music photographer, you are obviously a music fan. Where did music come into your life?

I started going to shows when I was like 12 or 13, and I took a photo class as a freshman in high school. And the first thing I did was take pictures of bands that either I was friends with or that were coming through the area — D.C., Maryland, Virginia. Once I started going to shows, it was four or five days a week, every week, for my entire life. Bands like Strike Anywhere and Darkest Hour were the first ones that were my age that were playing shows where people were losing it. Then I feel like I really started finding my place when AFI, Thursday and all those bands started coming around.

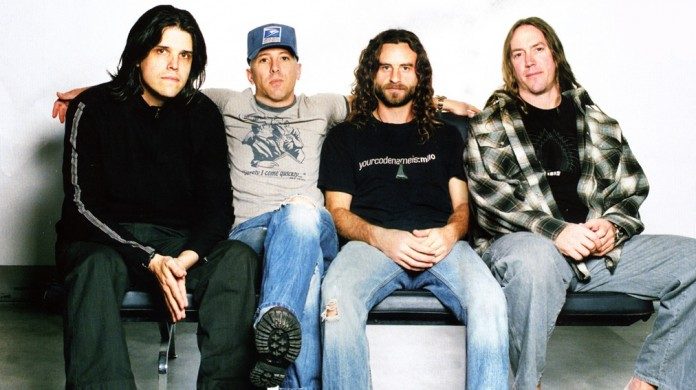

[Photo by Jonathan Weiner]

What made you want to pick up a camera?

When I first took the photo class, I just ended up signing up for it. I didn’t really know what I was doing or have any real interest. But once I had a camera and I was already going to shows, the idea of taking pictures with just my friends and yearbook things had zero interest to me at all. I’d do obscure random things, like in the woods or whatever.

Then I just started taking my camera to the shows because it made sense — it was what I was into. And I just enjoyed it. I liked the vantage point of what I was able to have from that versus just standing back. I had no intention of being a photographer for a living. I just didn’t know what else to do, and I enjoyed doing it. I didn’t want to go to school, and I wanted to go on tour and hang out with my friends.

How was it being around the Thursday and AFI camps as they were blowing up? Could you really feel what was going on at that time?

Oh yeah. I mean, I feel like that period is just so crazy. Every show you go to would be bigger and bigger. I remember Thursday played a show in Baltimore, and there were easily 300 or 400 people packed into a place that should only have 150 people. It was snowing outside, and it was so hot inside that every time I took the lens cap off my camera, the lens would just fog over. I think I spent most of the time sitting on the PA, keeping it from falling over instead of shooting anything. I think they went to Europe right after that and came back, and the next show they played was to, like, 2,000 people.

I have a lot of very fond memories of those times. I feel like any time I’ll talk about shows to people, they will start talking about things that we saw and the lineups. I’m very grateful to have gotten to grow up during that time. I feel like my purpose in shooting those shows was always to try to capture as much energy as possible. I’ve never been very into just straightforward photography; I’ve always had to make it something more. At the time, I was really into long exposure and experimental flash stuff. Everything was always trying to do shutter drags and trying to get lots of crowd involvement. I like to think that everything I took had the energy of the show.

You say that as a live photographer, your ambition was always to capture the real energy of the show that’s going on. As a portrait photographer, which is obviously where your work has moved to over time, what do you see as your role?

I think my strength and weakness at the same time is I do a lot of things. I’m definitely not somebody that’s like, “Oh, this is the one single thing that I do.” I really like lighting, and I really like personality. I’m not a big fan of making anything perfect. Typically with portraits, I want to show a feeling of that person. I want everything to be a collaboration. If I walk into a room and have a very, very specific plan of shooting a portrait of somebody that I’ve never met before, then I feel like that’s a disservice to what we could actually make.

[Photo by Jonathan Weiner]

In the scheme of things, we’re spending 20 minutes, an hour, three hours or whatever together, and then we’re all moving on, and that’s the end of it. But in that time, myself and whoever the subject is, we’re the only two people that can make that exact image in that exact moment. And I’d like that to be portrayed. I don’t want to see a photo that has no feelings.

Are there any artists you can point to that you feel a particularly strong connection with when you get in a room together, that allows you to bring out the best in them and they bring out the best in you?

I feel like my longest relationships are with Green Day, Brendon Urie and Andy Black. We all just work very well together. We just get it, I guess. I have a bunch of people that I’ve worked with fairly regularly over time. Jason Butler is a good example where, whenever he needs something, he’ll call, and we’ll start talking. We’ll go back and forth for about 10 minutes and end up on the same general idea that we were both thinking of. I feel like those are always the days that are the most fun and easiest because each person just makes the other person better, rather than fighting to get something that hopefully everybody likes.

[Photo by Jonathan Weiner]

For those artists that you don’t know or are shooting for the first time or have never had a relationship with, what kind of preparation will you do?

I think it depends on who the artist is on what my approach is. Depending on what the job is, I’ll have some references of what we’re trying to do already, but I’ll look into who they are as people. I try to learn about where they came from and what music they personally like. I always look at any old photos of them, just so I know what’s been done and what I like and what I don’t like. It’s super helpful to see what their habits are and how light reacts to their face and things like that. I always listen to their music — obviously, that influences their actual image.

[Photo by Jonathan Weiner]

Sometimes people’s image versus the music doesn’t match, or maybe the record cycle’s different, so I try to do as much research into what they’re currently on as possible. Sometimes, I’ll see everything they’ve done, and I want to do something completely different. Other times, I’ll just be influenced by something I saw or heard that I want to portray in them.

You mentioned one of your longest relationships is with Brendon Urie. The AP cover that you shot underwater is one of the most iconic images of him, ever. Can you tell us about creating that image?

That’s one of those ones where if it was the first time I’d ever met Brendon, that shoot probably would’ve never worked. Luckily, we were friendly enough that both of us could trust each other and do something that’s much more difficult than your standard “just look good” photo. We did a trial run a week before, learning what it was like to shoot underwater and how to light it. That way, when I got to his house, I had something of a plan. We spent probably an hour in the water, just me and Brendon, and we were getting as much as we could before he ran out of breath each time, and until his eyes got red and we couldn’t shoot anymore.

[Photo by Jonathan Weiner]

When you’re working on a job like that, do you have a sense in real time of what you’re creating? Can you take the frame and know immediately that you have nailed what you were trying to capture, or do you need to live with the shots for a period of time after to really understand what you made?

I guess it’s a little bit of both. I try not to overshoot. I like to have in mind what I’m trying to achieve and get it done as fast as possible. In my experience, most people don’t really like to do photo shoots. Some people do, but I don’t like having photos taken of myself. I know it’s not the most comfortable experience, so I try to keep it fast.

Plus, the longer anything takes, the more stale it is; the more somebody is just going to be going through the motions. It’s normally the most off guard you are, the better it’s going to be. The longer we sit, the more it becomes just a simple photo. That said, I don’t think I’ve ever once thought when I’ve taken a photo, “Oh, that’s iconic.” My mentality is very much, “I like what I just did. OK great, let’s move on.”

I think when artists are willing to commit fully to something, it translates into work that holds up. It’s not something that could be made by anyone at any time; it’s something that had to be made at that very moment in those exact circumstances. The other images that really hold you captive are the ones that are just the right time and place — ultimately, a moment in time that cannot be recreated.

I think that is an interesting notion when you consider the Lil Peep images that you captured for his album artwork for Come Over When You’re Sober. Images often take on a different meaning in different contexts. Do you look at those images in light of his tragic passing and see something different from what you did at the time?

There’s an interesting thing where because of the approach that I have, of just taking everything [one] shoot at a time and then moving on, I don’t always grasp things that will take hold. So that shoot, for example, came about very naturally. A friend of ours was managing him and had been trying to put me together with him for a while.

[Photo by Jonathan Weiner]

It just finally came together where his apartment was right down the street from my old apartment, and he called me to come over to do his album art. I spent a couple of hours with him and created something cool. I thought they were great images, but I had no idea where it was going to go. For that shoot to then have the life that it’s had, I would have never expected. It was a very fun shoot, and I feel like we were able to show a side of him that you wouldn’t always be able to see because of how vulnerable he made himself.

There’s one such example that comes up every year. I did a portrait of Mitch Lucker that ended up being the last professional photo ever taken of him. I think he passed away three days after we took the photo, which was him on his motorcycle on a cliffside with the sunset behind him. I don’t even remember what the feature was for, but him then passing away in a motorcycle accident three days later, it takes [on] a drastically different meeting. I guess that’s the interesting thing about photography in general: It freezes a moment in time, but then it also evolves over time. Every time you go back and look at an image, you’ll find something else, like it was waiting underneath to be unfolded as life unfolds.

You’ve shot a plethora of musical legends in your time, from Ozzy Osbourne to Smashing Pumpkins. How hard is it to keep things fresh and to bring something new out of people who have stood in front of a photographer’s lens thousands of times?

I think for me, it’s become natural, but I like to think there’re thousands of photographers, and with a digital age, it’s even more saturated than ever before. If you were to put 10 people in a room, all with a camera with one subject, every single one of them would take a different photo. Everybody’s eye is so different. I like to think, at least, if you have something to say, your vision is going to be different to anybody else’s.

[Photo by Jonathan Weiner]

As long as you’re not trying to be somebody else, as long as you’re doing what it is that you’re seeing, that’s the strength to it. I don’t think I’m a better photographer than anybody. Every photographer is a valid choice for any job because each of us is going to see something completely different and deliver something completely different. It’s more difficult for me to shoot the same artist over and over again than it is to try to make something different to what anybody else has seen. If I shoot Billie Joe Armstrong 10 times, then it’s more like, “OK, how do I make this look different from things that I’ve worked on?”

How do you make it different?

I think as I evolve as a person and an artist, so do they. Over time, everybody’s coming at something from a different place, whether it’s in their life or if their record cycle is different, or something’s changed from when I saw them six months ago to what I have now. I normally take that and adjust. Life keeps everything fresh.

[Photo by Jonathan Weiner]

How do you think your photography has changed with how you’ve changed as a person?

I evolve every month. I think every experience that you have changes the way that you see things, whether life has changed or technology’s changed. I try to take inspiration from everything I see, whether it’s a movie or an album cover or another person’s photo or lighting that I saw out somewhere. It’s ever-evolving. I feel like the last couple of years, especially, I’ve really tried to focus heavily on doing a lot of things that I first learned how to do — experimental long exposure lighting and things like that, and to bring it into a more commercial setting.

I like the idea of being paid to do weird things. It’s very gratifying because I’m getting jobs off of the things that I taught myself how to do, not anything that’s technically proficient. That’s exciting. All of the resources exist now to do everything as perfectly as possible, and music is not perfect, so I like to grit it up a little bit.

![We Are The World (Official Music Video) [Enhanced Video Version] We Are The World (Official Music Video) [Enhanced Video Version]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/182f6dTagkU/maxresdefault.jpg)