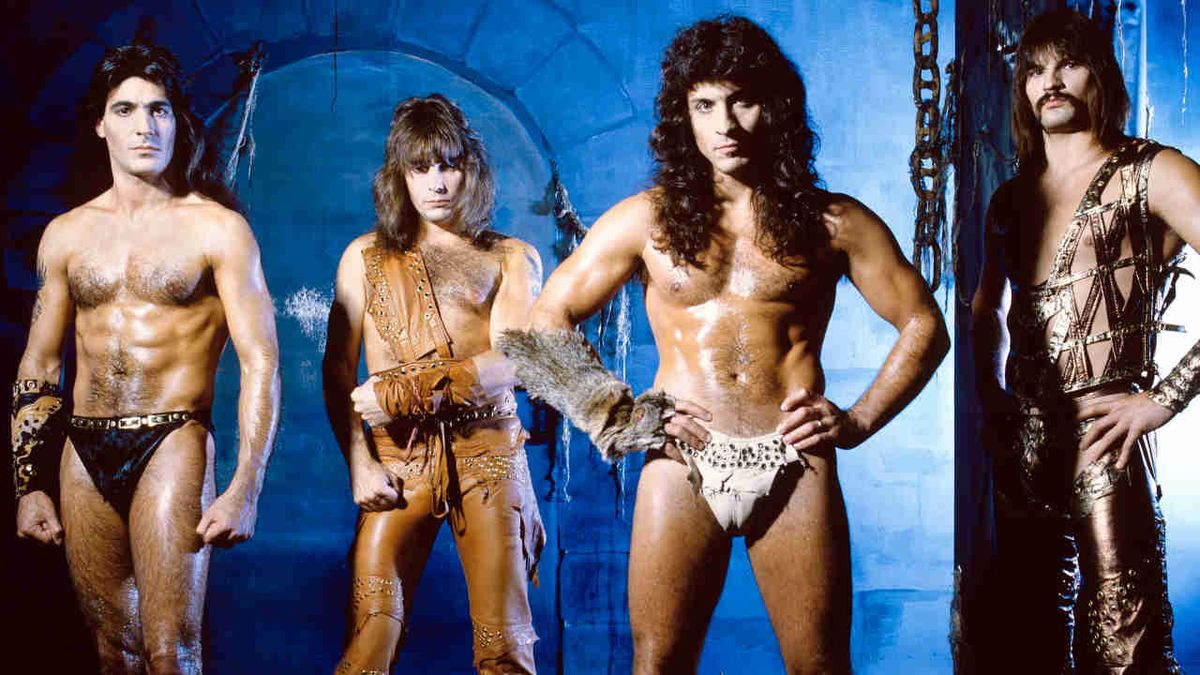

Kiss kicked off 1978 on top of the world. Since the release of their breakthrough Alive! album just over two years earlier, they had become America’s favourite rock’n’roll band.

In the previous 12 months alone they had put out two hugely successful albums in the shape of Love Gun and Alive II, played a triumphant hometown show at New York’s Madison Square Garden and prompted scenes to rival Beatlemania on their very first tour of Japan. The cover of 1976’s Destroyer had portrayed Kiss as all-conquering heroes, gargantuan generals offering up a rallying cry for the massed ranks of the Kiss Army.

To an entire generation they were The Beatles, the Stones and Marvel Comics superheroes The Avengers rolled into one, and backed by the most ruthlessly efficient merchandising operation ever seen. It was the devotion of the Kiss Army that would make 1978 the band’s most successful year yet. But as the Kiss machine started to overheat under the strain of internal tensions and external pressures, it was that same following who would desert them just as quickly, sending the band to the edge of the wilderness – a period which it would take many years to claw themselves back from.

“When the records are selling and the lunchboxes are selling and everyone wants to sleep with you, you don’t tend to be too introspective,” says Gene Simmons. “Of course there were problems, and of course it damaged us. But that’s easy to say now. It’s not so easy to pick up on at the time.”

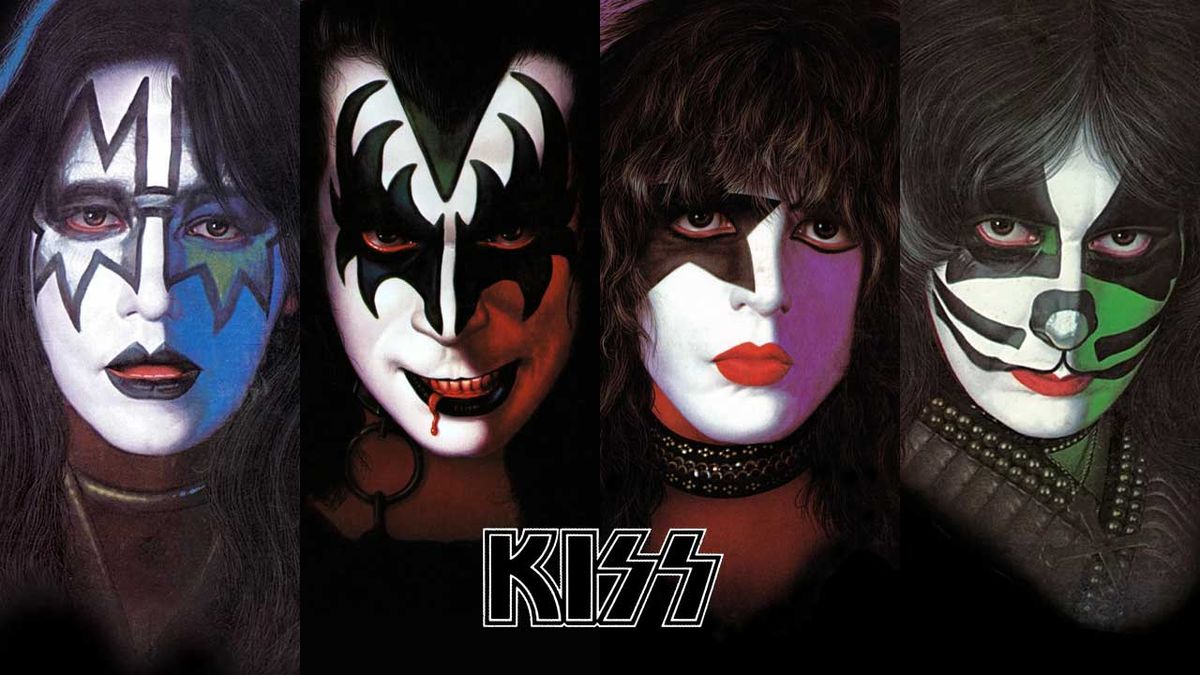

What the Kiss Army couldn’t see at the beginning of 1978 were the cracks in the makeup. A distinct fault line divided the band into two camps: in one, Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons were the no-nonsense, teetotal workaholics; in the other, Ace Frehley and Peter Criss were the loose-rolling, good-time party animals.

Early in their career all four had pulled in the same direction for the greater good, despite the differences in personalities. But their stellar success inevitably brought with it a whole set of problems. Chief among these were Frehley and Criss’s wholesale embrace of the party lifestyle. The combination of fame and financial reward proved to be a toxic mix for the pair.

Ill-equipped to handle the pressures of success, they numbed themselves with drugs, alcohol and coteries of hangers-on. In Frehley’s case this manifested itself in an inability to play to the standard Stanley and Simmons demanded. Alive II had featured three live sides, plus a fourth side comprising all-new studio material. But aside from his own track, Rocket Ride, the guitarist was absent from the new songs – his place secretly taken by Bob Kulick, a friend of the band who had originally auditioned for the guitarist spot when Kiss formed in 1973.

“It went quickly from being the Four Musketeers, and all for one and one for all, to people not pulling their weight and sabotaging what you want to do in an ongoing power-play,” says Stanley. “In plain English, wanting to fuck things up.”

While the band could apply a temporary sticking plaster to their internal problems, the external issues were less easy to control. Kiss had become victims of their own success, their fame and omnipresence creating a seemingly insatiable appetite for ‘product’. While Kiss-branded lunchboxes and bed sheets could be mass-produced ad infinitum, the music – the rock on which the whole operation was built, even if it increasingly didn’t seem like it to their detractors – was an altogether scarcer commodity.

The machine needed feeding, but in this case the supply couldn’t keep up with the demand. Inevitably there was pressure from their label, Casablanca, to strike while the iron was hot. In the absence of a new album, Casablanca assembled Double Platinum, a two-disc ‘best of’ whose title exuded bulletproof confidence. Among the remixed hits and fan favourites was a new version of the old classic Strutter, complete with a subtle but distinct disco rhythm. Little did the Kiss Army know, but it pointed the way to the future. “

Redoing that song was [Casablanca head] Neil Bogart’s idea, so we could get mileage out of Strutter if it was recut with more of a – quote-unquote – ‘disco’ feel,” says Stanley. “So we went along with it, but it was totally unnecessary.”

Released in April 1978, Double Platinum didn’t quite live up to its name – it sold a million copies that year, though sales didn’t hit two million until 2003. But what the band and label didn’t know was that it would mark a tipping point for Kiss.

Having conquered the charts, stages and supermarket foodcontainer aisles of America, the next logical step for Kiss was the big screen. In May 1978 the band began filming Kiss Meets The Phantom Of The Park, a film that was pitched to them by producers Hanna-Barbera as “Star Wars meets A Hard Day’s Night”.

The filming was an unmitigated disaster, not least because it took a sledgehammer to the already fragile relationships between the band members. Things got so bad that they weren’t on speaking terms with each other.

“By that point Peter and Ace had become unbearable,” recalls Gene Simmons. “During the filming of Kiss Meets The Phantom Of The Park they would sometimes not show up on the set. Peter was so indecipherable that they had to have an actor substitute his entire vocals. And this of course really pissed him off.”

“During filming, everyone’s telling you how great it’s going to be and that’s what keeps you going,” adds Stanley. “Then you see it, and it’s awful.”

Kiss Meets The Phantom Of The Park was indeed a stinker. The inane script, dodgy production values and the band’s own limited acting abilities showed they were human after all – something which defeated the point of what Kiss was all about. Its ratings were high, a result of the Kiss Army’s limitless desire to lap up anything with their heroes’ names on it, but on every other level it was a disaster.

Drug and alcohol abuse and out-of-control egos had pushed Kiss precipitously close to breaking up. Manager Bill Aucoin decided the best way to contain the flames of discontent was for each member to record a solo album.

“Ace and Peter were so upset with the band, with themselves, drugs, booze, all that stuff, that they were threatening to leave the band,” says Simmons. “Bill, bless him, was trying to keep the band together. Ace was unhappy. He was like George Harrison in The Beatles: ‘You’re not doing enough of my songs.’ So Bill said: ‘Why don’t you all do a solo record?’ Bill made it up on the spot. And Neil Bogart always loved big ideas, so he decided to stick out all four solo albums on the same day, with the Kiss logo in the top left hand corner.”

Released in September 1978, the four Kiss solo albums have gone down as a hubristic folly. That reputation does them a disservice. Frehley’s garage rock’n’roll album is rightly hailed as the best of the four and one of the great records in the band’s canon. Stanley’s Kiss-alike album and Simmons’s gloriously schizophrenic set have their charms. Only Criss’s R&B and lounge jazz-influenced album truly let the side down.

“We weren’t speaking at that point,” says Stanley. “We didn’t all kiss and hug and say: ‘Good luck with your album.’ It would be dishonest not to say that I wanted mine to be better than everybody else’s. But I worried about what all the other albums would be like. I didn’t need anybody to fail. I thought that failure would reflect badly on the band.”

He was right to worry. An administrative error meant that too many albums were sent out to record shops, meaning that thousands were returned unsold (prompting one wag to quip: “They shipped gold and came back platinum”).

Cumulatively the four solo albums sold as many as a regular Kiss record, but the perception was that they had flopped. The band weren’t strangers to failure – their first three albums had barely made a dent – but this was different. The weight of expectations from their fans, from the media, from their label and from themselves had been too heavy to bear. It was a major blow.

“Doing the solo albums was the biggest mistake we ever did,” says Criss. “It got to be: who’s gonna have the best album? Who’s gonna outsell whose album? That’s when that ego, that cancer, came in. I would be surrounded by people who would say: ‘You don’t need those fucking jerks.’”

But the perceived commercial failure wasn’t their only problem. The success of Ace Frehley’s solo single, New York Groove, had given the insecure guitarist’s ego a huge boost, precipitating further strains.

“The success of my solo album opened my eyes and made me a little more cocky,” the guitarist admits. “That planted the seed for me that eventually I was gonna do my own thing.”

By the time Kiss reconvened in the spring of 1979 to start work on their new album, Dynasty, the damage had been done. Literally, in the case of Peter Criss – the drummer had been nearly killed in a car crash the previous year. His injuries, combined with spiralling drug abuse, meant that he was either unwilling or unable to play on the album. He wrote and appeared on just one track, Dirty Livin’. For the rest of the album South African tub-thumper Anton Fig sat behind the drum kit. Criss’s situation only helped push tensions within Kiss to an all-time high.

“The band was falling prey to vices, compulsions and every kind of distraction,” says Stanley. “That album really is born out of that.”

If Kiss hoped that Dynasty would steady the boat after the misfires of Phantom Of The Park and the solo albums, they were out of luck. The album’s first single, the Stanley-written disco song I Was Made For Loving You, gave them a Top 20 US hit and helped push Dynasty itself into the Billboard Top 10, but its overt disco stylings had alienated the hard-core factions of the Kiss Army, who wanted the old sound back.

Worse, their merchandising success had come around to bite them on the backside: the lunchboxes and duvet covers had brought in a wave of younger fans, which further eroded the band’s credibility among their original following.

The subsequent Dynasty tour was fraught with major problems. Ticket sales were flat and some shows were even cancelled because of poor sales. A struggling economy was partly to blame, but so was the fact their hard-core following were put off by the growing presence of pre-teen fans drawn in by the head-spinning array of Kiss merchandise.

The band’s sinking credibility wasn’t helped by the fact that Gene Simmons had been seduced by Hollywood, and was now a fixture in the gossip columns with his new girlfriend, Cher. Kiss had committed the cardinal sin: they were no longer dangerous.

The band entered the 1980s as followers rather than innovators. The huge and loyal fan base they had built in just three years was shrinking to its bare bones. None of the albums that followed – 1980’s unloved Unmasked, 1981’s over-reaching Music From The Elder, 1982’s faintly desperate compilation Killers, and even the same year’s artistically sound but commercially unsteady Creatures Of The Night – could patch up the holes below the water line.

Peter Criss left in 1980, and was replaced on drums by Eric ‘The Fox’ Carr; Ace Frehley followed him out two years later, and mercurial six-stringer Vinnie Vincent stepped gingerly into his predecessor’s custom-made platform shoes.

“The interesting part about failure is you don’t realise your own participation in it,” says Paul Stanley. “We were looking around ourselves going: ‘What’s happening? And how can it possibly be happening?’ But we’d lost the plot. We became immersed in the trappings of success, so we were clueless. We were rich and we became complacent. We lost our backbone. People weren’t wrong for abandoning the band. The band had abandoned itself.”

Not everything was lost. The fan base might have been depleted in the US, but overseas it was a different matter, with Kiss fans in South America, Australia and Europe picking up the slack. Kiss’s artistic and commercial fortunes were partially restored by 1983’s Lick It Up, which coincided with the band taking off their make-up and reinventing themselves as MTV-friendly pretty boys (or at least as pretty as Gene Simmons could get).

While their diehard fans kept them afloat through the decidedly lean 1980s, the days of a vast and devoted Kiss Army were behind them – at least until the original band reunited, in make-up, in 1996.

“Did we lose our way?” Gene Simmons poses the question. “If you’re talking about the music, or the profile of the band, or our sales, in America, then yes. But if you’re talking about the band adapting and surviving and clawing back a fan base that most other bands would have lost, then no. We stayed true to ourselves.”

Kiss headline Download Festival this weekend. They also appear on the cover of the current issue of Classic Rock, with four limited-edition covers available (opens in new tab). This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 196, in May 2014.