In all of the interminable books, memoirs, articles and TV documentaries contemplating punk rock, there’s one thing they all seem to agree upon: that punk killed progressive rock. “Almost overnight, after the Sex Pistols prog rock came to a halt,” declaimed one pundit in a recent BBC documentary. Very well phrased – but totally untrue.

The fact that Pistols frontman Johnny Rotten once wore a Pink Floyd T-shirt with the words ‘I HATE’ scrawled in biro above the band’s name is always held up as evidence that punk was some kind of reaction to prog. Yet Rotten (as John Lydon) was a huge fan of Hawkwind, Van Der Graaf Generator, Can and various other bands whose progness was never in doubt. The idea that punk ‘had to happen’ because a whole generation was idly fuming away at the complexity of King Crimson or the overblown theatricality of Rick Wakeman’s – admittedly daft – staging of King Arthur & The Knights Of The Round Table on ice is just absurd.

As a crop-haired angry young man myself, I can’t recall ever wasting a minute of 1976, ’77 or ’78 thinking about how much I hated prog. Like most of my contemporaries I was having too much of a good time to really give a toss about prog, disco, rockabilly, pub rock or chart pop one way or another. There were too many other things in the world to hate. If there was anything musically that I couldn’t stand it was the constant diet of crap novelty records and golden oldies and smug DJs that ruled Radio One and Top Of The Pops in those days.

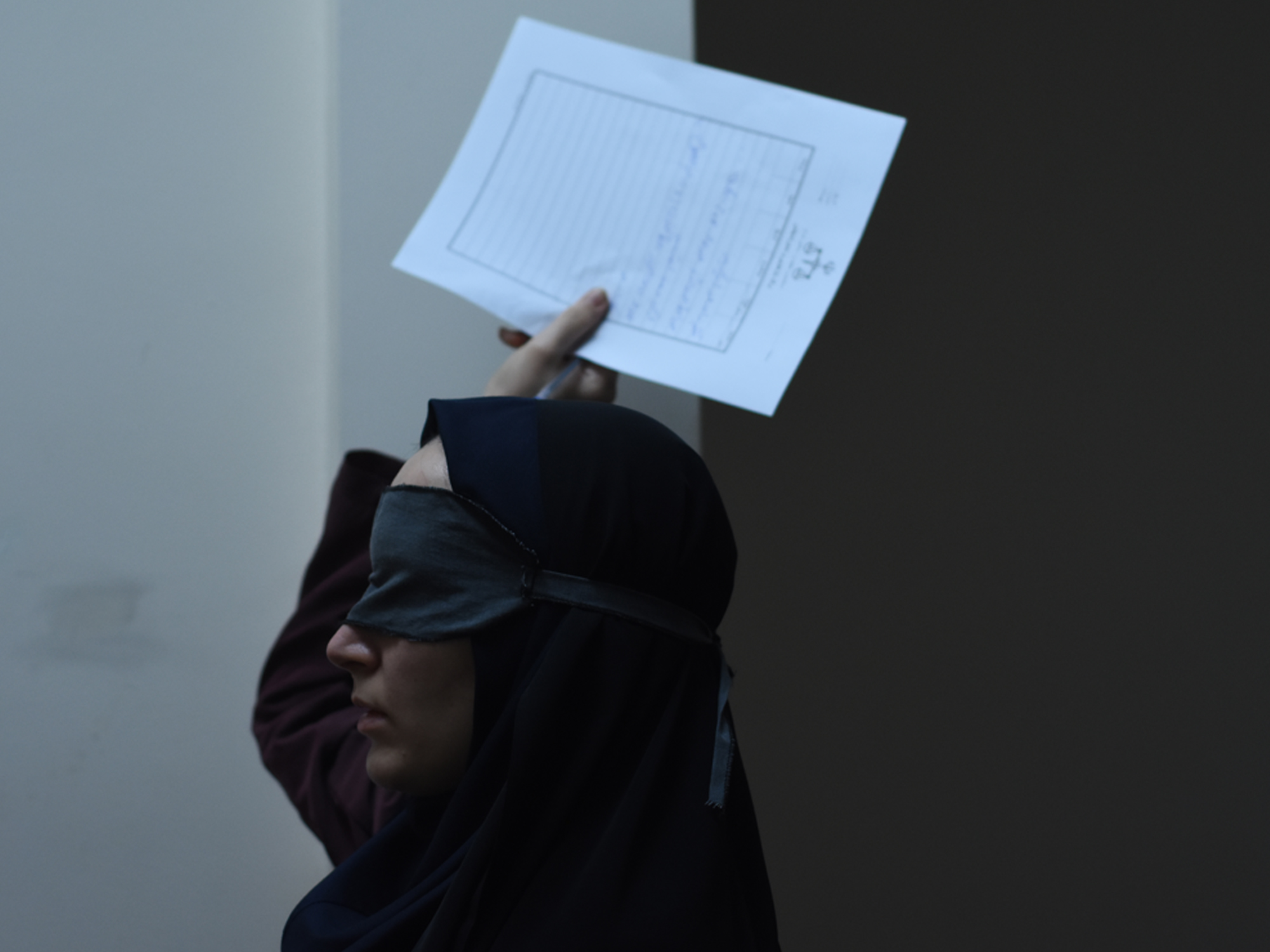

It was in the pages of NME, Melody Maker and Sounds that we were told that prog was the class enemy and encouraged to feel hatred. This was a revolution and, to paraphrase Lenin, what use is a revolution without firing squads? The thesis was that punk was a product of the salt-of-the-earth discontented proletariat, while prog was made exclusively by evil, right-wing toffs, and consumed only by Tory voters, fox hunters and those addled by false consciousness.

The reality, of course, was that while prog certainly had its share of former public schoolboys, at least the prog rockers were honest about their origins while people like the privately educated Clash frontman Joe Strummer felt that it was important to fake a prolier-than-thou past for themselves. At my comprehensive school, as well as a small smattering of punks, the popular artists of the day in 1976 were Frank Zappa, Mahavishnu Orchestra and – for some reason – The Incredible String Band. Conversely, the boys from the nearby fee-paying school were always trying to convince you that they were ‘too street’ to listen to anything more complicated than The Ramones, and that their spare time was spent sniffing glue, getting nicked by the pigs (maaaan) and smashing the state.

The attitude of prog musicians to punk was sometimes pretty condescending: Rick Wakeman allegedly sent a letter to the head of his label, A&M, asking to have the Sex Pistols dropped; Roger Waters made it clear that he hated punk; the lack of musicianship was decried. You could sense that they felt threatened, though obviously they needn’t have. Outside of the fantasy world created by the music press, it was prog that really ruled.

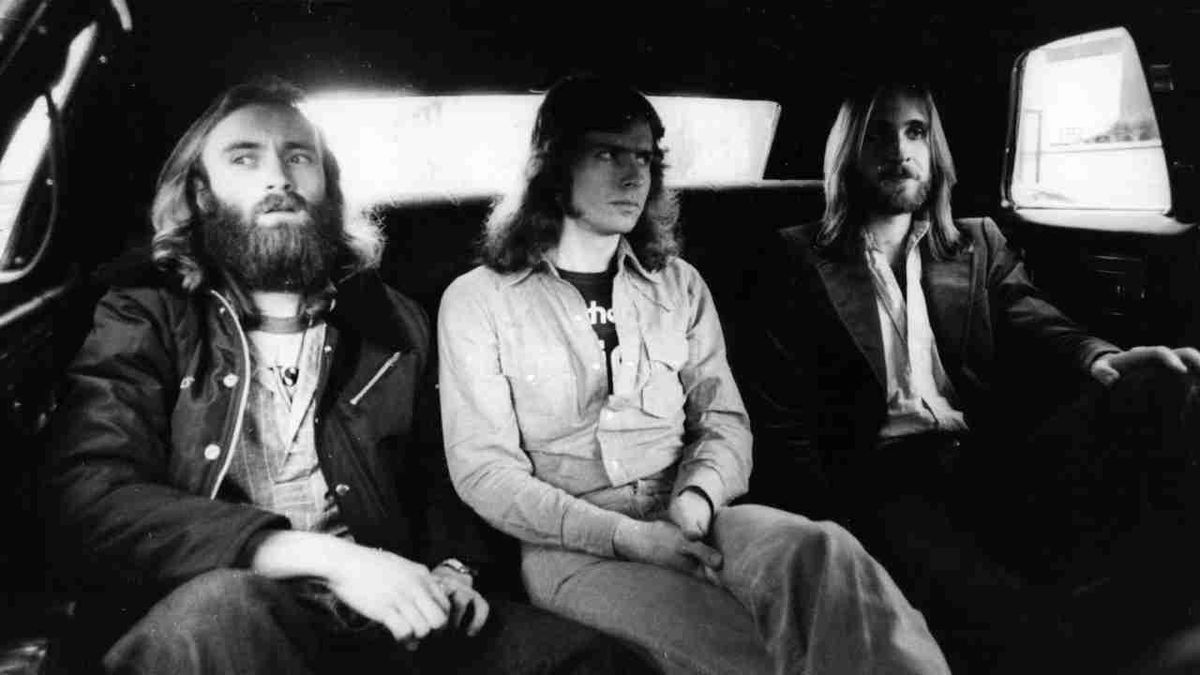

In the official history, 1977 was the year of anarchy in the UK, The Clash, no future. But it was also the year of Rush’s A Farewell to Kings, Pink Floyd’s Animals, Yes’s Going For The One, Genesis’s Wind & Wuthering: all Top 10 albums, all accompanied by massive tours, some the bands’ biggest ever. In the same period that saw the Pistols shoot and burn, not only did prog not die, it actually enjoyed one of its golden ages.

In the last years of the 70s, prog continued to outsell punk both on album and live. The decade culminated with one of the most massive prog albums ever: Pink Floyd’s The Wall. Around the time, new bands like UK, IQ, Pendragon, Twelfth Night, Marillion, After The Fire and Pallas all formed, while a realignment of prog’s superpowers created bands like Asia. It says much about the hubris of the media that, having failed to notice these bands, there was a sort of collective assumption that they didn’t exist. But with practically no press, radio or TV coverage anywhere, these bands regularly sold out shows and shifted millions of albums.

What’s more, away from the stadium-level bands, the thriving UK progressive underground continued to make challenging and innovative music: Soft Machine, Henry Cow (and successor band The Art Bears), Van Der Graaf Generator and Bill Nelson (formerly of Be Bop Deluxe and later Red Noise) made some of their best albums around this time.

Perhaps even more interesting were the bands who emerged in the immediate aftermath of punk who tried to make music that did more than repeat the same three chord formula. Cabaret Voltaire from Sheffield incorporated electronics, sampling and Hawkwind-like light shows; Glasgow’s Simple Minds, particularly on their Steve Hillage-produced 1981 double album Sons & Fascination/Sister Feelings Call, incorporated many elements from classic Genesis along with krautrock, disco and the avant garde; Ultravox, on their third classic album Systems Of Romance, made an album that seemed to continue the direction that Roxy Music abandoned after For Your Pleasure.

The fact that many of the post-punk generation were making a new kind of prog was not lost on some. “It’s bloody Curved Air,” sneered Nick Lowe when asked about Siouxsie & The Banshees, whose first three albums definitely pushed the boundaries of punk rock to their limits. And when Wire – arguably a synthesis of Ramones-style minimalist punk and high-prog complexity – recorded a 15-minute track called Crazy About Love for a John Peel Show session in 1979, Peel grumbled that it was a step backwards.

Today, prog is almost all-pervasive. There are so many bands – from the Dream Theater prog metal school to the experimental post-indie rock of Radiohead, to leftfield superstars Tool – who can all be termed prog, and who are indeed comfortable

with the tag. Pink Floyd’s Live 8 reunion not only stole the show but saw their album sales go through the roof afterwards, while the influence of King Crimson, Floyd and Yes is everywhere. (King Crimson themselves still make seriously cutting edge music.) Not bad for something that supposedly ‘came to a halt’ in 1977.

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 97, August 2006