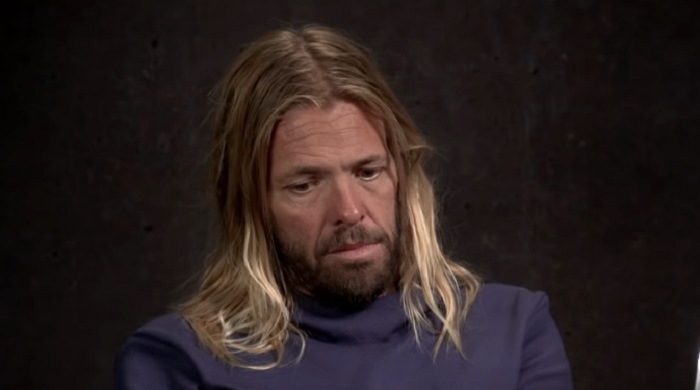

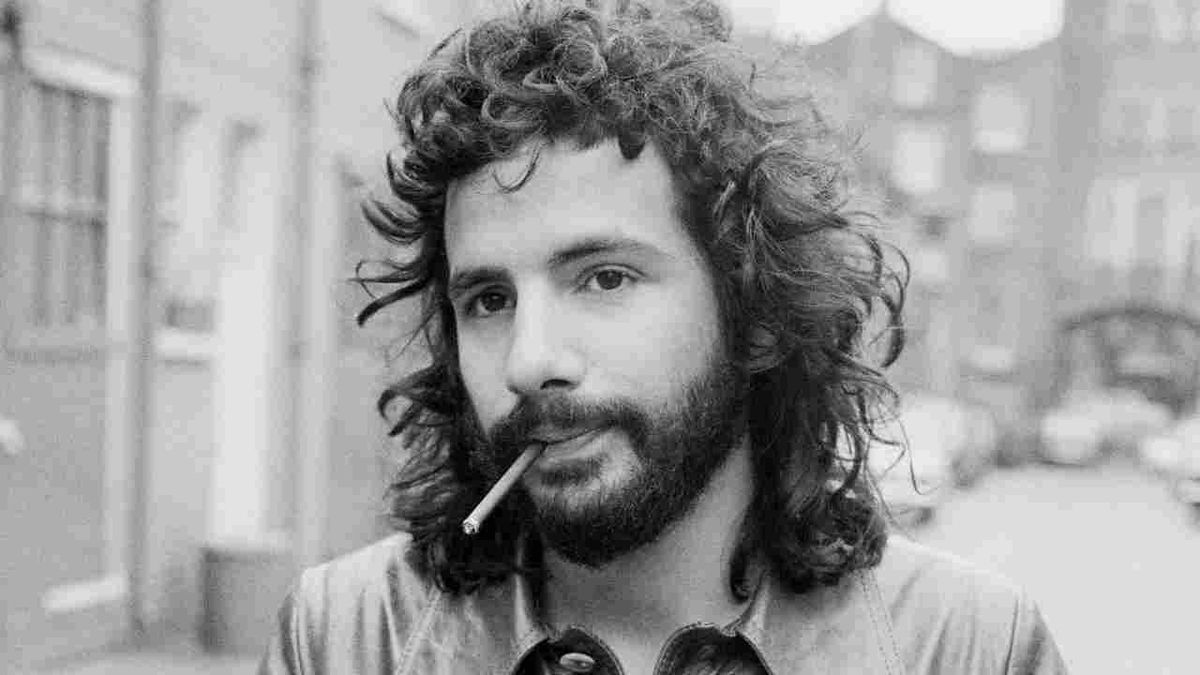

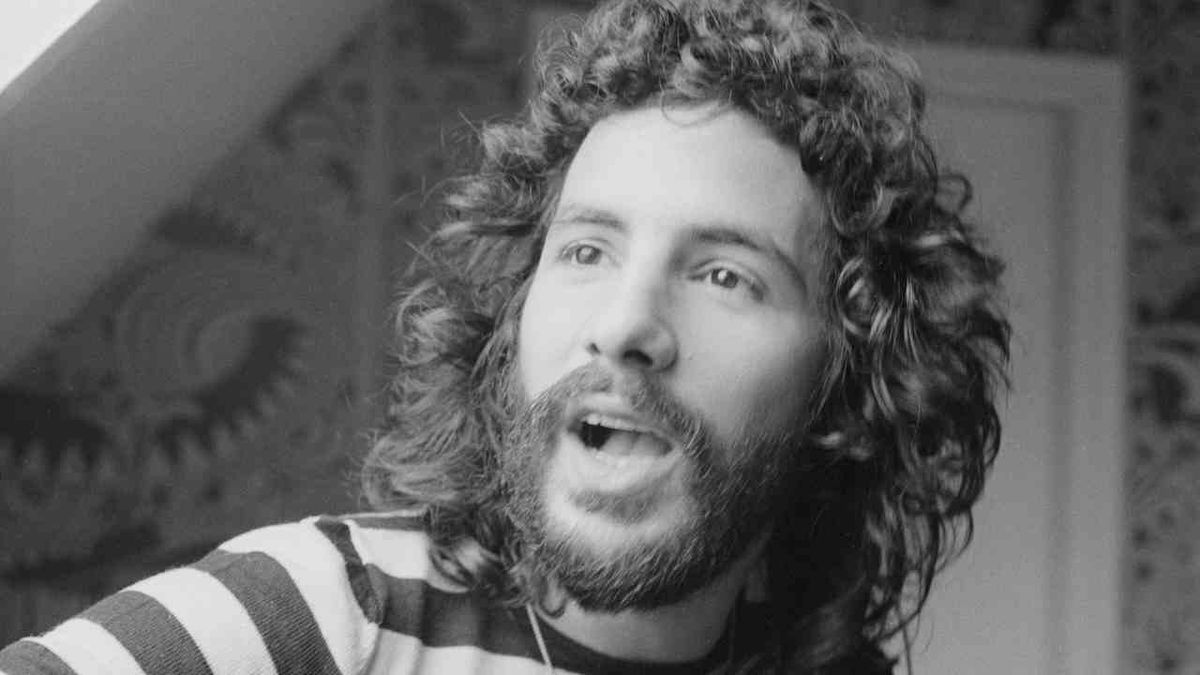

Cat Stevens was one of the most successful singer-songwriters of the late 60s and 70s. But then a near-death experience prompted a conversion to Islam, a change of name to Yusuf Islam and a retirement from the music industry. In 2004, a few months after he made his tentative return to the stage, he looked back over a career like no other.

Here’s how Cat Stevens used to get high before a show: “You need to loosen up before going on stage. So to have a drink beforehand was very natural. But you can overdo it, and then you can’t sing in tune. So I found that using a certain amount of oxygen after a couple of beers or whatever could put you in just the right spot. But you’d still be in control. It was just a strange little recipe I worked out. It was to get me lucid. So I knew exactly what I was doing and playing.”

OK, it comes pretty low down in the annals of rock’n’roll excess, but his audience could sometimes be forgiven for thinking that he might have taken something a little stronger. On the DVD of his 1976 Majikat tour of North America, he gets carried away when the lights get turned on the crowd: “You’re beautiful. I’m so glad it’s you and not them. Whoever they are. Who are they, anyway? They are we, man, they are we. We are me. I am… Who am I?”

This little monologue comes shortly before he advises us: “If everybody could love Alfred Hitchcock the world would be a better place.”

Maybe the world would be a better place if we all took a hit of liquid oxygen once in a while? “That was me trying to connect, trying to relax between songs,” he says with a chuckle. “I think I was a comical fellow in some sense. A lot of people didn’t know I had a very funny side to me. I enjoyed a good laugh. But most of my songs were serious.”

But as for getting out of it before a show, don’t even think about it. “I was far too much of a control freak,” he says.

The Majikat Earth tour was about as big as it got for Cat Stevens. He’d ridden the crest of the singer-songwriter wave through the first half of the 70s alongside the likes of James Taylor and Carole King, and he was now playing to 15-20,000 people a night at arenas around America.

He was selling millions of records, too. Hip cult heroes like Nick Drake, John Martyn and Richard Thompson (all of whom were signed to Cat’s record label, Island Records) may have been the darlings of the rock media but their total combined sales came nowhere near one Cat Stevens album.

His appeal was particularly strong among the bedsit generation. “Particularly the lone bedsitter who was trying to figure it all out, the way I was,” he says. “And the terms of reference had changed in the seventies. It was a new age and we were defining that age. And singers and poets do in some sense speak for the soul of a generation.”

Cat Stevens’s deceptively simple philosophical vignettes and maddeningly catchy melodies were as popular with women as they were with men. Which meant that a Cat Stevens album was an essential item for any bedsit boy making his first tentative moves in the mating game.

Once you’d invited a girl back for coffee and she was perched nervously on the edge of the bed while you gathered up the previous week’s clothes from the only chair in the room, the sight of a strategically placed Tea For The Tillerman cover would reassure her that you were, indeed, a boy who was in touch with his feminine side. This was the signal for you to get in touch with her feminine side. And yet the spiritual comfort Cat Stevens was providing for his audience was doing nothing for him. “I still had a gigantic hole to fill in my life,” he says.

He began backing away from the music business. By the end of the 70s he had converted to Islam – and had changed his name, to Yusuf Islam.

For many years Yusuf Islam refused to acknowledge Cat Stevens. But recently they have re-established a relationship. Yusuf Islam is now happy to talk about Cat Stevens. He even brought him out of retirement at the beginning of 2004 to perform at Nelson Mandela’s AIDS benefit concert in South Africa.

Cat Stevens is not his original name. He was born Steven Georgiou in 1948, the son of a Greek father and Swedish mother, and grew up in the Bloomsbury area of London where the family ran a café. “I went to school in Drury Lane and part of the fun was peeking into stage doors and scenery workshops on the way home,” he remembers. “Covent Garden, Denmark Street, Soho – those were my playground haunts.”

The first record to leave its mark on him was Laurie London’s He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands, a cover of a gospel song by a 13-year old boy that was a big hit in 1958. “He was one of the first child stars of the pop era. My brother turned me on to him. I think they were at the same school. And my brother popped this idea into my head – ‘You could do this’ – and I remember thinking, yes, maybe I could.”

By the time Steven Georgiou went to Hammersmith College to study art in 1965 the British pop explosion was at full blast. But it was the London folk scene that initially attracted him. “I was watching people like Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, Davey Graham,” he recalls. “And Paul Simon, who was there for a while. James Taylor was another who came out of that scene.”

He played a few folk club dates as Steve Adams, trying out his own songwriting style. “I was influenced by musicals. Living in the heart of theatreland I was just overwhelmed by the power of musicals. That’s where a lot of the ideas for my songs come from, and that’s why some of my lyrics are slightly left-field. They come from an angle that’s broader, part of a bigger storyline. I Love My Dog is a completely new take on a love song.”

Watch On

That was the song that Steve Adams played to Mike Hurst, an independent producer who’d been a member of Irish folksy trio The Springfields along with Dusty Springfield. “I went to his flat in Kensington and there was a Greek guy there who was actually an American producer, and he was nurturing Marc Bolan. And he kept saying: ‘No, no. Marc Bolan is the thing!’ But I visited Mike again later and he was going to go to America and try his fortune there, but he spent one last burst of energy on a recording session for Decca doing I Love My Dog. And that’s where it all changed.”

That was when Steve Adams changed into Cat Stevens. And then I Love My Dog nudged its way into the Top 30 in late 1966, helped largely by airplay from the offshore pirate radio stations.

“They would play anything and they helped to launch many careers, mine among them,” he says. “The BBC would never have gone along with some of those things. It was still the Light Programme. There was no Radio One.”

He was whisked straight back into the studio for the quirky, hook- Matthew & Son which was soaked in orchestral arrangements and shot to No.2 in February

1967, beating another of his songs, Here Comes My Baby, which had been snapped up by The Tremeloes. Suddenly, Cat Stevens had developed into a very hot property indeed.

The following month he found himself on a 25-date package tour trekking around the UK in the company of Englebert Humperdinck, The Walker Brothers and Jimi Hendrix. “At the time it seemed quite natural to me, although looking back on it, it was amazing,” he recalls, “I remember someone shouting: ‘There’s a fire on stage! Hendrix is burning his guitar!’ And we rushed down to the wings to see what was going on. We’d never seen anything like that.

“But off stage Hendrix was such a nice, gentle character. We had some…” he pauses, searching for the right word… “some very quiet moments together on tour. He was very pensive. You’d see him sitting down in a club sometimes, just thinking to himself.”

Cat Stevens seldom had that luxury. Togged up in his dandiest Carnaby Street clobber, he was dispatched on to the promotional treadmill for his next hit single, I’m Gonna Get Me A Gun, and his equally successful debut album, Matthew & Son, that, unusually for the time, consisted entirely of his own songs. Meanwhile, P P Arnold, backed by The Small Faces, was having a hit with another of his songs, The First Cut Is The Deepest.

He was certainly enjoying the trappings of the pop star lifestyle at that point. But he was also increasingly aware of how little control he had over his own career. It wasn’t just the crass publicity shots for I’m Gonna Get Me A Gun that had him dolled up in a cowboy hat brandishing a pistol; he couldn’t even play guitar on his own records.

“There were a bunch of musicians in the studio who interpreted your own music for you. I couldn’t really communicate with them because I didn’t speak the language. You had to know how to write dots and I didn’t know how to write dots. I only knew what I wanted it to sound like.

“It seemed to me that I had to get more control. And that’s what it was all about – my struggle with Mike Hurst, the record company and my agent was to try and find my own identity. Because I had music and ideas which hadn’t been heard yet.”

However, nobody was bothering to listen while the existing formula was so successful. And even when the hits started tailing off and the second album, New Masters, failed to chart at the end of 1967, there was an old-fashioned solution at hand.

“My agent, Harold Davidson, wanted to put you into pantomime if you weren’t having hit records any more,” he remembers with a laugh. “That was the next step as far as he was concerned – to get me to play Buttons.”

Stevens was saved from this fate by what he calls “divine intervention” – not the only time his life would be radically changed in this way. On this occasion it was tuberculosis that struck him early in 1968 and took him out of action for nearly two years.

“Immediately I was extracted from the whole music scene and given time and space to reflect, and decide a little bit more about my future,” he says. “And one of the goals I set myself was to find out a bit more about ‘The Truth’. It was an archetypal spiritual adventure. And I joined it.

“My convalescence gave me a chance to grow and develop… to grow a beard, which I didn’t have before. And symbolically that was to change my identity,” he explains. “When I came back I found a whole new group of friends who understood me for being more than just a pop singer. I was more of a poet – and I had more to say.”

One of his new friends was American actress Patti D’Arbanville who would inspire two of the songs – Lady D’Arbanville and Wild World – which would relaunch Cat Stevens’ career. Other songs came from a project for a musical that never made it to the stage.

“We came up with an idea about the Russian revolution, which we called Revolussia. And we had Nigel Hawthorne as one of the writers with us. It was dealing with change. But the strongest concept, for me, was idealism. What is the human ideal? And out of that came songs that were to be the new breed of Cat Stevens composition. Father & Son was one of them, Maybe You’re Right, Maybe You’re Wrong was another.”

He realised that his new songs would stand a better chance with a new record label. “I went back to see if I could match my expectations with Mike Hurst in the studio. We tried, but it never happened. And that’s when we tried all these different ways of getting out of the contract. One of them was to come up with a thirty-piece orchestra concept. And then they let us go – willingly!”

Watch On

Ironically the album he recorded after he’d signed to Island Records was stripped right back to basics. “It wasn’t consciously constructed that way,” he says. “It was just a natural result of shaving things down to the bare minimum. The songs had such important meaning to me that I didn’t want anything to confuse it, to makeit cloudy. So it was acoustic guitar, drums and bass.”

It also confirmed that Cat Stevens was very much a solo artist. “I couldn’t be part of a group,” he says. “I had tried it early on but it didn’t work. I realised that I was born to be solo.”

Mona Bone Jakon didn’t make the album charts when it came out in July 1970, even though Lady D’Arbanville was a Top 10 hit. But Stevens now had the creative freedom he’d craved, helped by producer Paul Samwell-Smith: “Chris Blackwell, the head of Island Records, was just so generous to artists, allowing them all this space to develop. I was even given the freedom to design my own album sleeves, which was fantastic.”

Whether such freedom benefited the Mona Bone Jakon album cover with its painting of a crumpled dustbin with a tear coming out of the lid is questionable. It might have made more sense if he’d stuck to the original title – The Dustbin Cried The Day The Dustman Died – but then again it made even more sense to change the original title.

Some bedsit boys believed that the Mona Bone Jakon title was an enigmatic code for a male erection, a rumour that Stevens is quick – though not too quick – to deny. “No, nothing like it. I mean, all rock songs in some sense have got a sexual connotation. That’s what rock’n’roll itself is all about. Ask Muddy Waters what he meant by a mojo. What is a mojo? And how do you get it working? And all the mumbo jumbo that went with it. It was kind of trendy to leave yourself unexplained back then. Dylan has been doing it ever since: ‘What are songs about? About three minutes.’”

The somewhat downbeat, hesitant tone of Mona Bone Jakon was remedied just five months later by the more assured Tea For The Tillerman. “Some people over here weren’t quite sure whether to believe what had happened when I came back,” he says. “To me it was just as natural as growing the beard. I had simply matured.

Other people were saying: ‘What’s going on?’ I think that’s the cynical side of the record business. They couldn’t quite understand it. But in America, where they had never really heard me before, they understood immediately. And it all happened.”

Once Tea For The Tillerman gained a foothold in the American charts, it American charts it stayed there for the next 18 months, more than twice as long as it stayed in the UK charts. Stevens’s search for a spiritual meaning from a mean material world articulated the confusion felt by many people at that time with songs like Father & Son, Where Do The Children Play, Hard Headed Woman and Wild World. Cat Stevens was a pop star again, even bigger than before, only this time it was on his terms.

Had he realised what a genre-defining album he was making at the time? “No. I was just following my heart, and the music was coming out and was being dressed absolutely appropriately with the musicians that I had, and kept very sparse and pure. It was a very purist period of songwriting and recording. I had a feeling there was something special but I didn’t know how people would take it.”

They took it with great enthusiasm, along with the follow-up, Teaser & The Firecat, which yielded three big international hits: the rousing Peace Train, the sublime Moonshadow and Morning Has Broken, a Victorian hymn that was stripped of its pomposity but not its dignity, as well as the beautifully concise opening track, The Wind.

Stevens was now able to control his career from a position of strength. “To be heard you have to be a bit powerful,” he says. “And power brings money and the ability to be able to do it your way.”

After two massive albums in the space of 10 months and a triumphant American tour with an 11-piece orchestra, Cat Stevens could afford to ring a few changes for the next album, Catch Bull At Four, in 1972. “I became a little bit harder, a bit more produced. I wanted to experiment with sounds. I was into more keyboards and less guitar. I had to keep generating my own interest. I didn’t want to become a puppet of my own making.”

Success had not made Cat Stevens any more gregarious, however. “I was still very much on my own,” he admits. “But my songwriting thrived on that very introspective condition. I didn’t feel so alone when I was writing. I guess I was in some kind of place where there was an unseen audience. But they were there…whatever that means, whatever that symbolises. I remember when I wrote those words in Sitting: ‘Sitting on my own, not by myself.’ That’s the kind of feeling I had.”

Catch Bull At Four was the first Cat Stevens album to top the America chart, one place higher than it reached in the UK. “And then I realised it was all going terribly wrong,” he laughs. “Or a little bit out of control. So I did another whole ‘let’s do something different’ thing. And I went to Jamaica and made Foreigner.”

Watch On

Foreigner was certainly different, and not just because of the location. Stevens temporarily dispensed with his band and producer, recruiting local musicians, adding a trio of backing singers including Patti Austin and handling the production himself. As if that weren’t enough, the first side of the album consisted of one 18-minute track, The Foreigner Suite. While his lyrical concerns remained the same, he now had a fear of being misunderstood that he articulated in the introduction: ‘There are no words I can use/Because the meaning still leaves for you to choose/And I couldn’t stand to let them be abused/By you, you, you.’

“Some people think it’s my best album, which is strange,” he admits. “But it just shows you that I had something more in me. I didn’t want to become a parody of myself.” It was also clear from some of the songs on the second side of the album, notably The Hurt, that fame and fortune, even on his own terms, was not providing the inner happiness he was seeking.

He couldn’t stop pleasing his fans, though. Foreigner got to No.3 in America and Britain. He was now so successful that he became a tax exile, although the huge tax bill that he would have paid to the British Government he sent instead to the UNESCO children’s fund and other related charities.

His choice of exile was unconventional too. He headed for the then-unfashionable Brazil where he fell under the spell of the music. “I don’t think there’s anything as detailed, intricate and beautiful as Brazilian music,” he enthuses. “It’s just so rich. I couldn’t quite make that kind of music. What I did was through my words more than anything else. Plus my melodies.”

Buddha & The Chocolate Box, released in 1974, is perhaps the last conventional Cat Stevens album. “It was to reassure people that I can do this thing if you want, but it’s not exactly where my heart is. Although many of the songs on that album were good and meaningful. King Of Trees is a lovely song, back to the Where Do The Children Play theme. And the same with Oh Very Young.

“But spiritually I was still searching. I was still casting my net as far as I could in the realms of inspiration and looking for answers. I delved into my own Greek ancestry and the heritage that I had. I looked at Pythagoras and tried to make some sense of the universe through numbers. And I came up with an album called Numbers which is still very profound.

“Some people like that album, but it’s a bit weird. It was also supposed to be a cartoon at one time that would have preceded the whole Lord Of The Rings trilogy. I was very influenced by Lord Of The Rings. Trying to get to the goal of life was what it was all about – the rings, solving good over evil.”

Numbers was the first Cat Stevens album not to make the American Top 10 since Mona Bone Jakon. But the Majikat tour at that time was the most spectacular he had yet devised. The brightly lit tent-like stage set enhanced the music and the support act of magicians and illusionists heightened the atmosphere.

“Whatever I wanted to do, I could do it,” he says. “I even had a tiger on stage as my support act when the tour reached Los Angeles. It was wild, but I could do it. However, it still wasn’t satisfying me.”

The contradictions between Cat Stevens’s spiritual quest and his pop star career were becoming increasingly manifest. The driving ambition that had got him this far was being supplanted by the need to control everything – right down to how his lyrics were interpreted.

There’s a moment on the Majikat DVD when he almost loses it mid-way through the show after a roadie gaffer tapes his mike stand – making it impossible to adjust – when he should have been seeing the joke. Apparently he had the chance to edit out the sequence but refused. “Greeks and ego go well together,” he says with a rueful smile. “I was becoming domineering. I wanted things to be like I wanted. And that’s when the Greek tragedy took over.”

He can’t pinpoint the moment exactly, but it was some time around the Majikat tour and he was swimming in the sea off Malibu when he realised that the current was dragging him out to sea. “All of a sudden I had no control whatsoever. I was about to drown. I saw my life disappearing in front of me.

“I cried out: ‘God!’ I’d always had, deep down, a faith in the presence of God, even though I couldn’t understand how to approach God. And I got an answer. And the answer was to give me back my life and then to be prepared to do something a little bit more real with it.”

It was divine intervention for the second time, although he didn’t act on it immediately. In fact his next album, Izitso, in the summer of 1977 seemed like a return to the Cat Stevens of yore, with the bouncy (Remember The Days Of The) Old School Yard – a duet with Elkie Brooks – giving him another hit single and another American Top 10 album. But it was the last hit single he would have, and Stevens’s true feelings were clearly spelt out on another album track, (I Never Wanted) To Be A Pop Star.

“Izitso was a strange, reflective kind of album,” he says. “By now I was reading the Koran and I was more concerned with what I was finding there. It was opening my eyes to so many new things.”

In December 1977, Cat Stevens formally embraced Islam and changed his name to Yusuf Islam. There was one more Cat album, Back To Earth in late 1978, which included the Brazilian-flavoured Nascimento from the end of his musical adventure, and the stage-musical-styled New York Time from the beginning. He didn’t promote it but it still got to No.33 in America.

In February 1979 Yusuf announced his retirement from music to devote himself to Islam. Which he has done faithfully ever since, becoming a prominent member of the London Islamic community, establishing the Islamia School and a hotel in Kilburn, and becoming president of the Islamic Association of North London.

But he has also been involved in more controversy than he ever was as a pop star. There was his non-appearance at Live Aid in 1985, either because of a dispute over whether he could be referred to as Cat Stevens, or because Elton John over-ran. There was his support for the fatwa against author Salmon Rushdie in 1989 – although his insistence that the laws of the country could not be broken, thus rendering the fatwa largely symbolic, was seldom reported (he subsequently denied that he supported the fatwa). Then there was his expulsion from Israel with his nine-year-old son as an ‘undesirable’ in 1990 – and his visit to Iraq later that year when he managed to secure the release of a number of British Muslims being held hostage during the first Iraq war.

In 1995, after 18 years of musical silence, Yusuf released an album on a label he’d formed: Mountain Of Love Records. The Life Of The Last Prophet was a spoken word story of Muhammad that included one musical performance by Yusuf. He followed that with Prayers Of The Last Prophet and an album of Islamic songs for children, ‘A Is For Allah’, which is used in English-speaking Islamic schools. Then there was his benefit album for the Bosnian Muslim community in 2000 called ‘I Have No Cannons That Roar’ that featured two songs written by Yusuf, one of them performed by him.

“I thought that the album needed to be a celebration of the victory and the survival of the Bosnian nation. So I came up with a compilation of Bosnian songs and I also contributed. That helped me to ease back and so coming back to the studio was that much more natural.”

In 2003, while producing an album by Zain Bhikha in South Africa, Yusuf worked on his first English-language song – a new version of Peace Train – since 1978. It was included on the War Child charity album, Hope, in aid of the victims of the second Iraq war. Yusuf’s statement on the album said: ‘As a member of humanity and as a Muslim this is my contribution to the call for a peaceful solution to the dangerous path some world leaders today seem to be taking.’

Yusuf also recorded a couple of new songs and a reworking of Wild World at the same time, the latter featuring a new arrangement that incorporated the Soweto Choir. That led onto his appearance at the Nelson Mandela benefit concert .

“I certainly don’t feel the need to rush off and do what other people think I should be doing. But there is still harmony left in me which probably has to come out.”

Yusuf is choosing his words very carefully here. Music is a controversial topic among Islamic scholars that provokes heated disagreements. Even some of Yusuf’s Islamic recordings have come under fire from militant Muslim clerics. Although Yusuf has softened his own stance on music that he took at the end of the 70s, he is still sensitive to hardline opinion. Apparently he does not own or play a guitar. But as he once memorably sang: ‘Can’t keep it in.’

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 72, October 2004