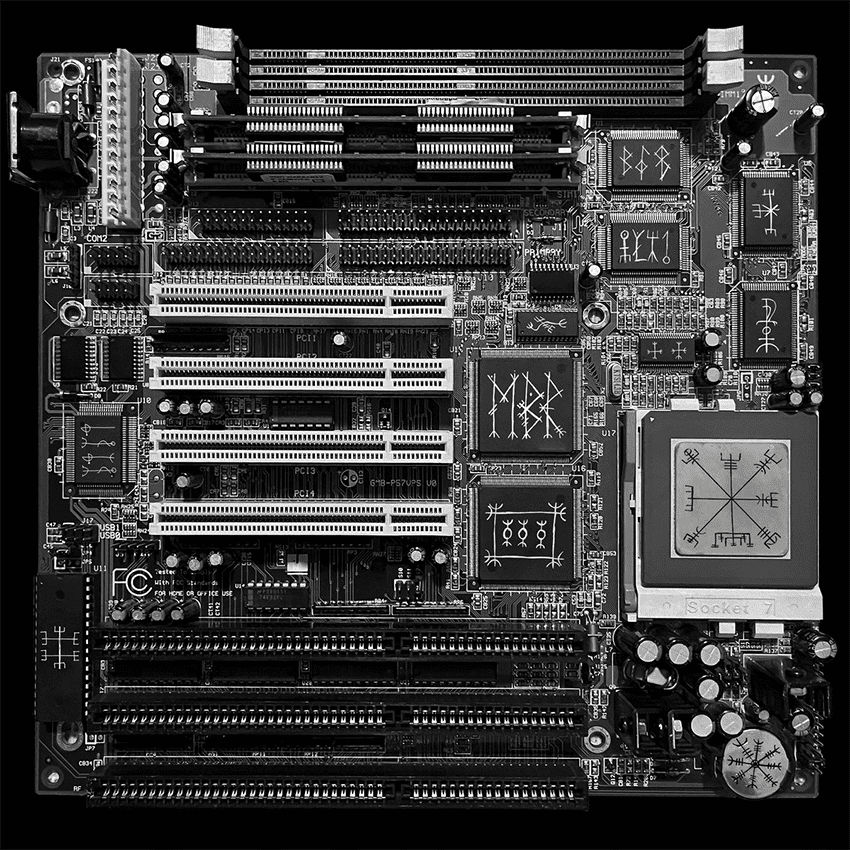

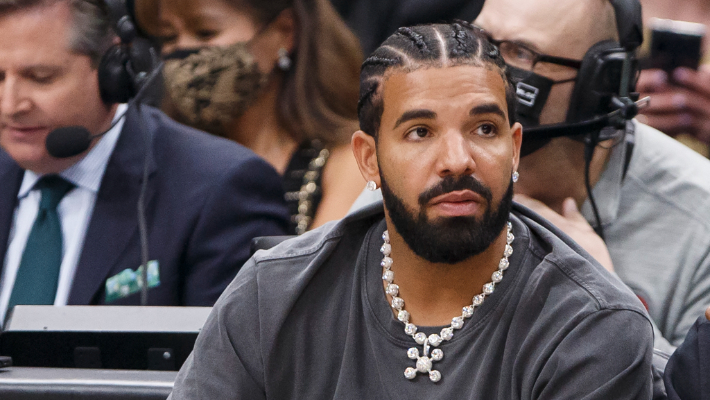

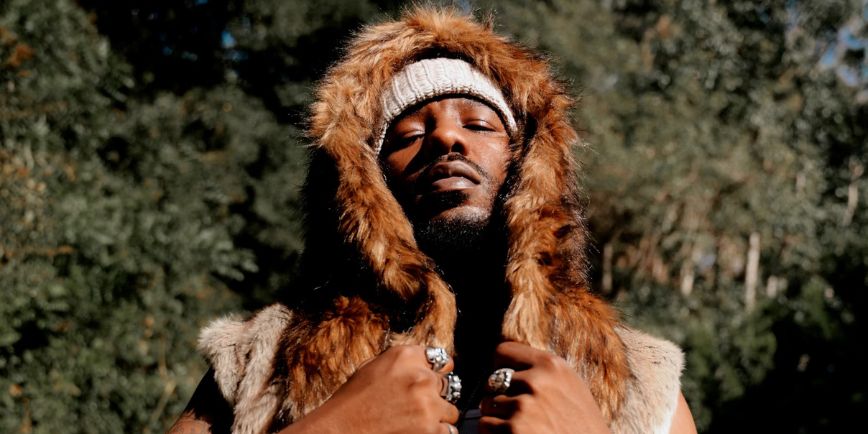

Photo by Stephanie Cabral

Ever since the first installment of Kill Screen, Decibel’s co-nerds have sought a consensus among our player characters on the parameters of what makes a game or console “retro”—and have failed miserably. Some have proclaimed that the demarcation for gaming’s modern era started as early as 1989 and as late as 2006, with many often landing somewhere in the middle. Today’s interview may not offer any answers, but certainly not for lack of experience. Victor Love, the mastermind behind Italian computer metal project Master Boot Record and the classical-leaning Keygen Church, has been hitting leaderboards since the days of his beloved Commodore 64. Having lived through the vast majority of home consoles’ eras, he finds himself less interested in semantics. To Love, it’s all music to his ears.

The son of a digital pirate with unlimited access to gaming’s exploding catalog, Love’s life was surrounded by games that those wearing rose-tinted VR headsets remember so fondly. Though a metalhead of the ’90s with a history in industrial dating back to 2003, it was while scoring his own point-and-click adventure game VirtuaVerse in 2016 where the code that would become Master Boot Record was synthesized. After releasing covers of gaming anthems from the likes of Doom, Castlevania, Duke Nukem and dozens more, MBR has signed with vanguards Metal Blade Records, contributed to OSTs and crossed the digital threshold into reality to bring their “100% Synthesized, 100% Dehumanized” sound to a live setting. Any longtime fan of video games and heavy metal knew that we could cross paths eventually, and with MBR’s new album Hardwarez pumping through our speakers, Love’s contribution to indie darling Vampire Survivors’ recent Ode to Castlevania DLC and planned upcoming tour of the U.S., there was a lot to discuss.

Interested in unlocking even more from this interview? Check out Love’s print-exclusive thoughts on AI’s place in art in the February 2025 issue of Decibel, due to hit mailboxes in late December and on newsstands January 7th.

What was your first gaming experience?

Very, very first? That was probably on this little handheld thing, the little ones with the LEDs, if we can consider them video games—of course we can. If we’re talking about ancient stuff, it’s really that—the little handhelds that we had back in the ’90s. If you’re talking about actual video games… [Pauses] It’s hard to say. Probably Rambo: First Blood [Part II] on Commodore 64. I was 8 years old or something like that. I remember that because my father bought Commodore 64 and it was like, What the hell is this? It was in 1986, I was 7 years old and it was one of the first games I installed. It was just the cassette. I remember that also because there was this loader with the music. It was so great for Rambo: First Blood. Otherwise, probably Ghosts ’n Goblins at the arcade or stuff like that.

Would you say that Ghosts ’n Goblins was the game that really got you hooked on video games? What would you say is the title that made you a gamer for life?

I can’t really say because I was a kid. I had been playing so many video games for several reasons, especially because my father being into [computers], he was also one of the biggest pirates in Italy, actually. [Laughs] It’s a long story. We had a computer shop, too, so I was playing so many video games. But it literally started with Commodore 64, so it was either Commodore 64, or it was the arcade at the bar, because there was this arcade just before the school. It was not actually an arcade. We didn’t have a real arcade in Italy until probably the early ’90s. It was just a bar, like a café. We have a lot of these snack bars here in Italy. Every one of these bars, they usually had, like, three, four cabinets with the arcade games, so it was either that or Commodore 64. Probably Commodore 64 because I don’t remember when the bar opened up with the arcades. It was either, like I said, Rambo or Green Beret.

Oh! Maybe it was this one. It was Impossible Mission. Impossible Mission was a platform game [where you were] going into the lift, and there was this thing at the beginning. It was like, “Stay a while, stay forever!” And then there was this scream like, “Rah ha ha ha ha!” with the Commodore synthesizer. It was so weird. [Laughs] It was probably one of the first synthesized vocals I ever heard.

Master Boot Record is deeply connected to Commodore 64 and Amiga 500. You’ve mentioned that your father owned a computer store and you had access to video games and consoles well after the Commodore 64 lifespan.

I had everything for everything. Like, literally everything on every type of computer and platform, starting with Commodore 64, Amiga, then MS-DOS, then consoles, PS1, Nintendo, you name it. I had everything!

What is it about Commodore 64 that is so important to you? Why is that the console that you keep going back to?

First off, it was not Commodore 64 that was my first computer, but Commodore VIC-20, which is pretty much the same. Commodore 64 is very important to me for several reasons, mainly because it was the first computer I had, my first “gaming” computer. You could also play with BASIC and stuff, but I was mostly using it for the games, of course. I was a kid. It is especially important to me because of the music, of course. The music on Commodore 64 was influencing me a lot, and I only realized this a long, long time after—just before making Master Boot Record. It was like 2016, I was 37 years old. In that timeframe of my life, I was going back to retro gaming for a bunch of years already, and I was rediscovering all these games and all the music.

Commodore 64 has got this special chip called SID [Sound Interface Device] chip, which has a very particular kind of sound. A concept that is also inside Master Boot Record is coming from Commodore 64, because of the limitation of the medium. Commodore 64 only had that channel, so the limitation of the medium inspired creativity. In fact, a lot of Commodore 64 music is very classical. It’s focused on melodies, because you didn’t have much. You had this shitty sounding drum. I love it, but it was not so much about the drums, it was more about the melodies.

This is a concept that I transferred to Master Boot Record. I always use the same sounds for all the records. They improved a little bit over the years, but essentially it’s the same sound set. I have a synth guitar, synth bass, chiptune lead and pads for the drums. Especially on the new album they are much better now, much better samples, I improved the synth guitar sound—on the new album, there are also real guitars—but the concept stayed the same, which is also the concept of crack scene and demoscene. It all started because they put these intros in the games that they were pirating, but the floppy disk did not allow much space. They had to create these intros in very little space that was left from the game inside the floppy, so usually it was, like, 64 KB or 4 KB. This is the limitation of the medium.

So, the demoscene and the crack scenes and all the competition between the groups—Razor 1911, Fairlight, Paradox, all the groups—were competing with each other since the beginning to make the best graphics in the smallest space. That is a concept that is connected to chiptune, demoscene, but it’s also part of pixel art. You have just enough pixels that you can create an image that’s low resolution, high imagination. I believe—this is just my opinion, of course—that it’s more artistic, in a way, compared to realistic art, because you have a very limited canvas and a limited amount of colors. Or, in the case of music, a really limited amount of sounds. For example, on Commodore 64, there are four channels, I think, so you can only have a limited amount of channels. Now we have unlimited channels, we have unlimited sounds. In synthwave, there’s so many different sounds, so many different things, so many different productions and stuff. But then it all sounds the same. That’s the big issue.

Even with a lot of classic movies, people say that sometimes having a very limited special effects budget or limited abilities to make huge CGI, you have to get really creative and you come up with something really great.

It also gives you a distinctive style. The tour poster that we just launched, the recent graphics that we had for the tours, that’s 1-bit graphics. It’s just pixels in black and white. Now you have a very precise style because of the limitation of the medium you’re working on. You have a very clear definition of the style you’re doing.

Iron Maiden is the example. They always have the same sound, they always use the same progressions. Some can say, “Iron Maiden sounds all the same,” but some others can say “Iron Maiden has their own sound.” I think that’s more important than anything else for a band. That’s why Master Boot Record has its own sound and way of doing things, and I’m never going to change it. Never. I mean, I can improve it. For example, this new album has real guitars. Of course, it was composed the same way as the other ones. I added the guitars because it was adding a lot. We did a lot of touring, and during the touring we realized that what we do on the new album is exactly the same thing that we do live. The mix that we bring for the back tracks is different from the album. It’s got less synth guitars because if we play the guitars on top, then it’s too much guitars, but that’s a technical thing. What we discovered during the tour is that it was just sounding better. It was sounding so powerful. The synth guitars and synth bass and electronics in general are very defined. They bring a very defined sound to the live show. But when you mix them together with the guitars and real drums, it adds a soul to it which is made of error, of imperfection. Together, mixed with the synths, it creates this sound which is massive and defined from one side, but is also alive, in a way. That’s why I improved the sound.

This is also something that characterizes a lot of the music in gaming. For example, if you take Mega Drive—you call it Genesis, right?—it has such a special kind of sound. You remember that? So metal.

Definitely. As soon as you hear it, you’re like, Oh, yeah, I know what that is.

For example, if you take Contra: Hard Corps’ music. It ’s so [mimicking crunchy guitar] dah dah dah, dah dah dah! That was the beginning! Not Contra in particular, but in general. The fact that a lot of the music in retro games… Also, it’s a bit funny for me because we call it “retro games,” but for me, it’s just “games” because there’s no retro about it. I live in that. [Laughs] But yeah, let’s call them “retro games.”

People talk a lot about retro gaming, but it’s so poorly defined. What would you consider to be “retro gaming”?

It’s very hard to say because one can say until PlayStation 1, probably? But then you also have GameCube, all that stuff. I don’t know. Probably from Windows 95? No, but Windows 95 was really very old stuff. I don’t know. How can you say that? Like, Silent Hill is retro gaming?

The time difference between PlayStation 2 and PlayStation 5 is actually longer than the time difference between Atari 2600 and Super Nintendo. And I [Michael] remember being a kid and getting a Super Nintendo and just being like, Oh my God, this is the hottest new technology ever. What is this Atari bullshit? Now there are kids who are growing up now that PlayStation 3 could be their first console ever. That could be considered retro gaming to them.

Yeah, it’s very hard to say. How can you say from this on it’s not “retro gaming” anymore? For me, it’s just “gaming.” You can define them as games for Commodore, games for Amiga, games for PlayStation, whatever, but you can’t really say what is retro gaming. In general, it is considered all the games from Commodore, Amiga, MS-DOS, PlayStation 1, Sega Mega Drive or Super Nintendo, that’s classic. And, of course, all the arcades—Neo Geo, the games only made for the arcade and all that stuff.

Maybe one can consider to delineate, you get a Pandora Box and all that is retro gaming, so whatever is after that is not retro gaming. But do we really need to say this? I don’t know. It’s just a way that people have to understand things.

People gotta put everything in a box. It’s the same thing with metal. People love to say, “What is death metal? What is black metal?” And it’s like, “What does it matter?”

You brought up a very important thing, which is also about our new album. This is why I decided to say “This is computer metal.” By doing so, I did something that I don’t like to do, which is to define myself, the music I’m doing. But I had to because they were mislabeling it all the time. There were a lot of people saying it’s synthwave, and I don’t think it’s synthwave at all. This not only created a situation where people are calling that synthwave, but it’s also creating a problem in the business because people think I am a DJ. People think that if they book me for a show, they think we are not a band, that we are not metal. It’s hard to get booked at metal festivals because they think we are synthwave. So, at some point I had to make a choice and say, “I don’t want to say it’s not synthwave. I want to say what it is.”

When we released the “CPU” single off the new album, everybody was writing “computer metal, computer metal, computer metal.” It made me think about when they wrote “black metal” in the store of Euronymous [Helvete]. It makes so much sense that instead of being written on a wall, it was written on the internet! It’s metal made with computers, but it’s still metal. And when we bring it live, it’s even more metal than it is on the album.

Going back to gaming, I can say that the music from games has been very influential for the creation of the project. When I created the project, it was essentially because I started to do this video game VirtuaVerse. It’s a point-and-click adventure.

Whenever I do new music, I always go and listen to a lot of different music to figure out what I want it to be influenced by. I started to listen to a lot of Commodore 64 music, demoscene music, crack music. To be honest, not much synthwave. It was in the same period of time that synthwave was going around, and of course, it had a little part in it—especially about doing instrumental music—but the big part was mostly about doing music that was influenced by retro game music. That’s because the game was a retro point-and-click adventure, so I wanted to have this sound in the game.

But when I was doing this, I wrote some songs that were a lot more metal. I was like, Hmm… maybe I create a project with this, and then I just released it on Bandcamp. A week later, it was first in metal on Bandcamp, and then it all started from there. It was in that moment, I was listening to all this music again and a wave of emotions that brought me back to when I was a kid listening to this music. I realized how much that has influenced me. It’s crazy, because the soundtrack of VirtuaVerse came out five years later. The music I wrote for the game is essentially the first album of Master Boot Record, but it was released only after. It had a very strange progression, in a way.

VirtuaVerse started out as the pixel artist, Valenberg, redesigning your Technomancy album with a pixel art aesthetic and then you decided to take that further and to actually make a game. You personally crafted the story and the characters and you hired somebody to handle the coding.

I didn’t hire him, we were just three friends. All the coding is done by Elder0010, who is a close friend of mine. He’s also into demoscene. He does demos for Commodore 64. He’s one of the best programmers I know.

What was the experience like actually creating a game after so many years of being such a big fan of games?

It was such a great experience. It was a lot of work, especially in the last year. We’d been crunching so much because despite that the game can seem a little simple in the way it is created, there’s so much text, so many puzzles, so much bug fixing. [There was so much text] and we translated it into eight languages, so it was a lot of work. But it was such a great experience because we would work on the game only when we had time. This gave us a lot of space to meditate on things. We changed so many things in progress—we thought to do some stuff in a way, then we changed it completely—so doing it over a lot of years really helped us to go where we wanted to go.

We wanted to bring back games like [The Secret of] Monkey Island, like Zak McKracken [and the Alien Mindbenders], like Maniac Mansion, like Indiana Jones [and the Last Crusade]. We wanted to bring it in the same way and the same difficulty that we experienced when we were kids. It was even more difficult at the time, because now you can just go on the internet and find a solution. But back in the day, you didn’t have this. There were either the books you could buy with the solutions—but I didn’t have any money to buy them—or you would just ask your friends. I can’t forget how many times I restarted Indiana Jones or Zak McKracken. I think it took me years to finally get to the end of it. It was so crazy.

What I like in point-and-click games is that you are playing the game when you’re not playing the game. You play the game and you get stuck, and when you’re stuck for a long time, you’re walking or having fun with your friends, and then you are like, Ah! Maybe I can try this! Then you go back home and try this and it works and it gives you so much reward.

Unfortunately, the thing is new gamers are really not used to this. They are used to “follow the fucking arrow.” So when we released the game, there were so many people pissed off that it was so difficult. The feedback was vastly positive, but there was always this 10 percent of people that were complaining about the fact it was so difficult. With the story mode, we removed 70 percent of the puzzles or something like that, and we created this story mode afterwards that you can play easier. There are much less puzzles and so on.

Now, I don’t want to be a boomer saying, “Oh, the new gamers are like this and the old gamers were smarter.” It’s like saying, “It was better when we had cassettes and CDs, and now we have Spotify.” It’s very hard to say what’s better because then you have, for example, guitarists like my guitarist Edoardo Taddei, who is 24 years old. He knows more music than I do because he’s on Spotify and he’s got everything. One can say today the gamers have got everything. They can either play new games or they can play old games. They are free to do what they want, so maybe they are even more lucky than we were. I was lucky because my father was a pirate and he had everything. But a lot of people didn’t have everything.

And that is, in fact, why piracy existed. In Italy, a lot of games were not distributed at all. So, what would you do if you wanted to play some game? The only way was to get the pirated version of it. Piracy is always the result of scarcity. Nowadays, piracy is almost nonexistent. A lot of people, of course, are pirating games, but a lot less than, like, 10 years ago. Me, myself, I don’t pirate games anymore. I have Steam, I buy them on Steam, whatever. You can find them at a good price and it’s completely different now. But back in the day, if you wanted to play one game, either it was not available or it was, like, €50 to play one very simple game and the kids didn’t have that money. It’s a controversial argument, but I think that piracy has helped a lot. We wouldn’t have all this retro gaming hype if it was not because of piracy in the same way that Metallica would not be so famous if there was not tape trading. Most of the bands I know, I have all their vinyl now, and I bought them. I’m a metalhead of the ’90s—Metallica, Megadeth, Sepultura, Pantera, whatever, you name it—all of them, I discovered them on tapes that some friend gave to me. It’s the same thing.

We’re also seeing game developers having so much more access to game dev tools. The indie scene is absolutely exploding with creativity now, and there is such an interest in this retro style of games. Does it feel authentic? Do you find that there are people out there that have that same mindset as you or do you feel like this is something that’s almost lost to time?

I don’t like to be a boomer saying, “It was better before,” or, “It’s better if the game designer has firsthand experience.” Take the case of Ultrakill. [Developer Arsi] “Hakita” [Patala] is quite younger than me. He’s a very smart person and he knows a lot of games, a lot of music. He’s a very 360-degree artist, and he developed this game pretty much alone.

Maybe he didn’t grow up with Doom or maybe he did, I don’t know exactly. But this doesn’t mean that he can’t make a great game anyway. Maybe somebody didn’t experience all the old games, or maybe has played some of them or only seen the gameplay videos, but didn’t play them directly. Still, they get influenced by this, and they want to create something that is new with the paradigms of the new world, but inspired by the old world. In some cases it can be cringe. Maybe the developer is not good enough, he can just be trying to copy a game in a bad way. On the other side, for example, Ultrakill is doing this genre called “boomer shooter,” but he put so much innovative stuff into it—so many crazy ideas, so many crazy weapons and so many really creative things. The concept that is behind Ultrakill, all the story that is behind it, is so great.

It’s a very exciting world we are living in because there’s so many tools. People can do so much stuff. People can learn so much on the internet.

Your other project, Keygen Church, contributed a number of cover songs to the new Vampire Survivors: Ode to Castlevania DLC. How did this come about?

This absolutely blew my mind because it happened in the simplest way: they just wrote me an email.

They were like, “We are doing this thing.” They didn’t say anything about details. They were like, “Do you want to be involved? We are doing an expansion of the game that will have some cover songs of very epic anthems of very famous video games.” I was like, “Yeah.” Then I had to sign an NDA. They explained it to me better, and it was such a great thing. I didn’t expect that, my mind was blown away. I’m a big fan of the game. I was playing a lot of that game when it came out, and then there was this Castlevania thing.

It was just perfect for what I’m doing, the perfect crossover: vampires, Castlevania, Keygen Church music, pipe organs, whatever. Keygen Church is inspired by music like Castlevania, all that type of game music, gothic music, vampire music. It was such a great experience. I like that they didn’t give me the very famous songs, but they did give me mostly songs from Michiru Yamane. She did a lot of [Castlevania:] Curse of Darkness and other stuff. She’s so great, she’s so classical and it fits very well. At the beginning, I was like, This is very hard to convert to Keygen Church, but when I was starting to do it, it was so inspiring for me. I did 44 cover songs with Master Boot Record. They are all for free online on YouTube, and for me, doing these cover songs is a gem. It’s a way to get influenced and to understand a lot of things that influence what I do in my original albums.

It was released when I was on tour. It was so crazy. I didn’t know what to do. Oh, my God. Oh, man. It’s so much stuff all together. I’m so proud of this, because it’s such an important game and it’s one of these indie games that really had a great success story. To be a little part of it for me, it’s a great honor.

Have you had the chance to play it yet?

I played a little bit of the DLC. Not so much, to be honest, I just got back from the tour, like, yesterday. I can’t wait to have more time because I want to unlock all the music. I still didn’t hear my stuff on the game because I have to unlock every character. When you unlock it, you also have a menu where you can pick different music. They added this thing [where] once you have unlocked it, you can change the music that you hear in the background, which is pretty good. Also, a big honor for me was the fact that they used my song in the final cutscene.

This is one that we typically ask at the very beginning, but we just got into it and we had such a great conversation that we didn’t want to interrupt: What games are you playing these days?

Really soon I’m going to play Frostpunk 2, because I’m a big fan of Frostpunk. I know that it was released, but I was on tour. Recently, I have been playing a lot of base-building games, for example, Workers and Resources: Soviet Republic. It’s very fun. I was playing Starfield. It was pretty OK, but I gave up. I played the latest Resident Evil, Dead Space, the remake. I’m a big fan of Total War. I was playing, of course, a bit of Ultrakill and Vampire Survivors while I was doing the soundtrack. I like these crazy games like Oxygen Not Included.

It’s a crazy fucking game. It’s a base-builder where you are in an asteroid and you create this base, but it’s all about the physics of liquids and stuff. You have to create environments that work with the physics of liquid, like carbon dioxide going down, oxygen going up, taking care of temperatures and stuff. You have to create this base on an asteroid, and then eventually you go out and you create rockets to go to other asteroids. It’s so crazy. I spent so much time on it. [Laughs] Then I played Elden Ring, Elder Scrolls. I played so many, I have so many games on Steam.

Also, I was playing Baldur’s Gate [III]. The guys from Baldur’s Gate are actually Master Boot Record fans. They were doing one video podcast, and they were wearing the Master Boot Record t-shirt.

That’s awesome. You must have been so excited!

I was so excited. They are such a great, great team. They also did Divinity: Original Sin. It was one of my favorite games. So great.

I love Metro, the shooter. I played all the [new] Resident Evil. Of course, sometimes I go back also to more classics like Shadowrun, that kind of stuff. I was a big fan of Star Wars, so I played Star Wars: X-Wing Alliance. A year ago I played the new System Shock, which is pretty cool. Another game I’m a very, very big fan of is Elite Dangerous. Do you know Elite Dangerous?

Yeah. It’s kind of scary because that’s one you can lose 1,000 hours in.

Yeah, I did. [Laughs] I did I think 500 hours of it. That is pretty cool because it was the first game that you could really experience virtual reality in a good way. Virtual reality is very bad for some games because it gets you dizzy and stuff, but Elite Dangerous, you’re just sitting on the fucking spaceship. I also have a joystick, the Logitech very complex joystick [Extreme 3D Pro Joystick]. You’re literally in this world, flying. It’s a very complicated game, but it’s more like a simulator. You go around planets, make missions, or maybe you go mining some asteroid to get the gold and then sell it.

Then there is a lot of lore about these guardians, ancient aliens. You go to some planet and there are these big monoliths and stuff. There is a whole story behind it and it’s very cool. Sometimes I spent like a week to jump from system to system to system to system to go get something very, very, very far. Then you get stuck there and then you have to calculate the jump manually because you can’t jump anymore! Dude, it’s so crazy.

Going back to the difference between retro games and new games, what I see in new gaming is unfortunately there are not much really new mechanics that are being created. Vampire Survivor’s success is because he created something completely new in its simplicity as a game. In Ultrakill, it’s still an FPS, but there’s so much stuff in it, so many genius mechanics. The problem is also that back in the day there was nothing, so when you did a new type of game, there was only your game. When Dune II: [The Building of a Dynasty] was released, it was the first RTS base-builder, like Command & Conquer. Everybody’s mind was exploding about that game. The same with Monkey Island or Zak McKracken, Maniac Mansion or Another World—I think you call it Out of this World. It was this cinematic platformer, a little bit like Prince of Persia. It’s one of my favorite games. I think it’s one of the best games ever created in that every different stage there was something different happening, as a game mechanic. That was very special.

Right now, all the games are the same. Maybe it’s a third-person shooter or third-person action-adventure. The so-called action-adventures are all pretty much the same, but I still enjoy them. Resident Evil is, of course, different from Assassin’s Creed, or Assassin’s Creed is different from Doom Eternal. They are, of course, different from Fallout, which I’m a big fan of. Fallout 3 and 4, especially. Also the first one, when it was isometric. I’m a big fan of isometric, the games like XCOM, turn-based strategy. I love the new XCOM, the new iteration but I also love the old one. I tried to play it again and it was so fucking hard. The first XCOM [UFO Defense] is so hard! It’s incredible, I don’t understand how I could play it. I finished it when I was a kid, and for real, I try to play it now, I die every time. All the time, time was running out and the aliens have won. I was like, How was I able to finish this game? It’s incredible. The good and the bad things of the new and old games.

Hardwarez is available now via Metal Blade and can be ordered here.

Order tickets to become 100% dehumanized at the January 2025 tour at the official server.

Follow Master Boot Record on Bandcamp, Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.

Sign Up for the Kill Screen Newsletter

Get the latest in Kill Screen interviews, videos and contests delivered right to your inbox with zero latency!

“*” indicates required fields

![Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video] Mason Ramsey – Twang [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xwe8F_AhLY0/maxresdefault.jpg)