When video games take on popular movie and entertainment franchises, results can be mixed at best. For every Arkham City, there’s an Avengers. For every Knights of the Old Republic, there’s a Superman 64.

Read more: Every Foo Fighters album, ranked from worst to best

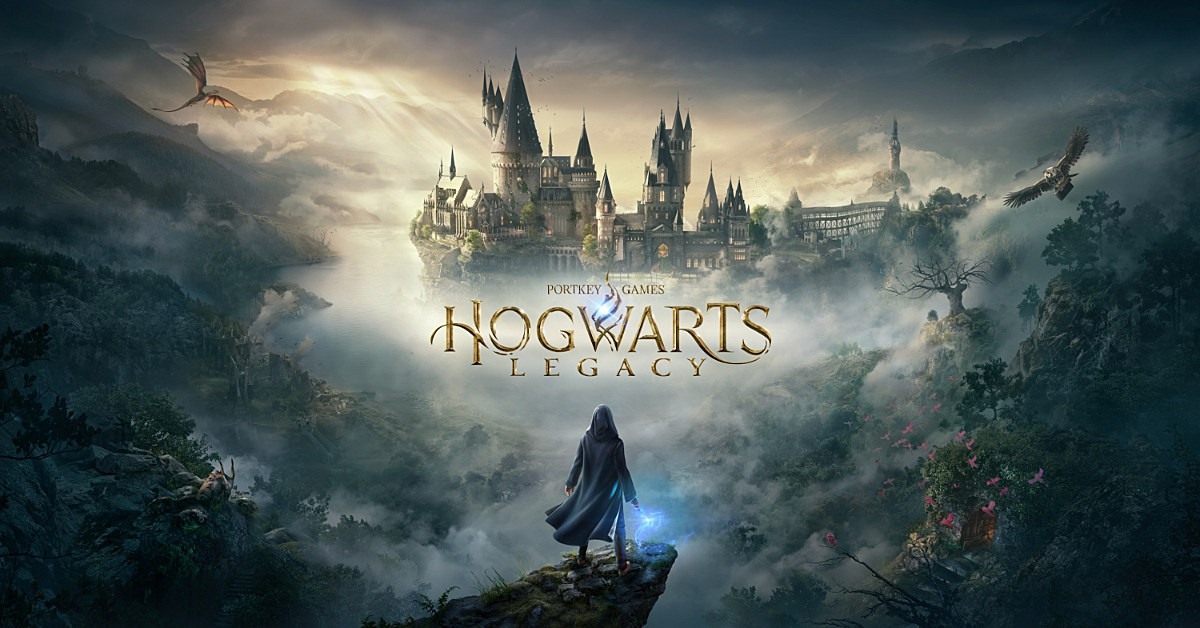

So it’s understandable why Harry Potter (or “Wizarding World,” as it’s now going by) has generally played it pretty safe. Sure, there were the movie tie-in games that virtually every blockbuster film received in the 2000s and early 2010s and the LEGO titles that modern cultural juggernauts receive, but nothing outside of the tried and true formulas. Until now.

Hogwarts Legacy takes gamers back to the 1800s for an action RPG with a brand new story within the Wizarding World. The familiar setting and new characters seem to be working out so far, as the game has already broken a variety of sales and gameplay records for titles only available on current-gen (PS5 / Xbox Series X/S) consoles and PC.

While the gameplay itself is frequently what’s to be expected from a large-scale AAA action RPG, the setting and environment is every bit worth the price of admission for Harry Potter fans. Hogwarts and its surrounding areas look, feel and sound as good as expected, and that’s largely thanks to a score that wouldn’t be out of place in any of the feature films.

Alternative Press spoke with the two people most responsible for that score, composer Peter Murray and composer/sound designer J Scott Rakozy, to learn more about it.

Considering that there’s already so much music within the Wizarding World, how did you add unique new tunes while still making sure it existed in the same realm?

Peter Murray: Many composers have contributed to the Wizarding World franchise, and each one has added their own voice to it. When I wrote a cue for the game, I would often begin by choosing a few reference tracks from the Harry Potter and Fantastic Beasts films. I’d listen to them and make sure I understood their feel, harmony, and instrumentation, and I’d sketch out a few ideas. The music I wrote would often start out sounding fairly similar — at least in terms of style and mood — to the tracks from the films, but the more I would develop and flesh out the piece I was working on, the more individualized it would become.

At the end of the day, we really only had a couple of rules when writing for the game, and it all boiled down to “fit the moment.” If it worked, it worked. If reference tracks and style guides weren’t getting the music where it needed to be, we would write until it sounded right.

J Scott Rakozy: What was probably the most challenging part of this whole project is that the bar is set so high by the likes of John Williams and Jeremy Soule, so we needed to find a balance of paying homage to these great composers. I purely wanted to bring back those magical moments and elements that we, as kids, enjoyed when we first watched the Harry Potter movies or played the Harry Potter video games — and that relied heavily on melodies.

I feel like today’s scores have become a secondary character to any media — whether it be games, movies or TV shows — and are merely driven by textural elements and padded ambiances. When you think back to video games from the ‘80s, ‘90s and early 2000s, the music was a main character, driving the emotions of the story and gameplay. Granted, the sound chips back then were pretty limited on how many channels of sounds or voices they could play at once, so the music was an integral component. I did a lot of research diving into not only the Harry Potter scores by John Williams, but going back to his scores for Jurassic Park, Jaws and lesser-known films to find inspiration and discover new ideas. It wasn’t a matter of finding a unique voice, but rather finding a familiar voice we’ve all heard from yesteryear and bringing that back for this new generation of young gamers to experience and enjoy.

How was working on Hogwarts Legacy different from other titles you’ve worked on?

Murray: Hogwarts Legacy is by far the highest-profile project I’ve worked on, and the music of the films is one of the highlights of the whole franchise. I think there’s been a lot of pressure to deliver something that lives up to that legacy and holds its own. That pressure may come from fans, but it also comes from us. We wanted to do a superb job, and we hoped that the score we wrote wouldn’t just be a side dish to the other music of the Wizarding World. We really wanted our offering to be worthy of the franchise.

Rakozy: What made this soundtrack so different from any of the projects I’ve worked on is that I got to explore the ideas of John Williams, study his scores and figure out specific elements that made his scores sound unique. My previous works have been influenced by Harry Gregson-Williams, John Powell and Thomas Newman, but I never limited myself to just those styles. My projects have been all over the map, from synth-driven scores to folksy chipper bluegrass to chiptunes. I typically like to challenge myself and explore all these possibilities, so I don’t get pigeonholed into one genre or style. With this opportunity, I wanted to stretch myself orchestrally and see what I could really do.

Were there any moments or issues that surprised you when working on the soundtrack?

Murray: One of my tasks on the project was to go through everything and find tracks to put into one moment or another in the game. Let me tell you, there is a ton of music in there. Peaceful drones for exploration and calmer moments, sketches and variations of melodies for possible themes and leitmotifs, five to 10 different mixes of countless combat tracks, an album’s worth of atonal harp gestures to be used in stingers and short moments of emphasis, and literally hours of waterphone sound design.

Rakozy: For me, it was the looping factor. That always trips me up when working in games. I come from a background of doing commercials, short films, documentaries and production library music. There’s a beginning, a middle, an end and that’s it. But in-game music — especially at this caliber and complexity — I would write seven to eight minutes worth of music and try to figure out transitions, and also looping points before those transitions. But then the score has already modulated 5-6 times, and I have to figure out how to modulate it back to loop seamlessly to the beginning and not have the player notice. It’s a ginormous jigsaw puzzle for me.

I could’ve kept it really simple with ambiance tracks — stay in the same key and call it a day — but that wouldn’t have done it justice.