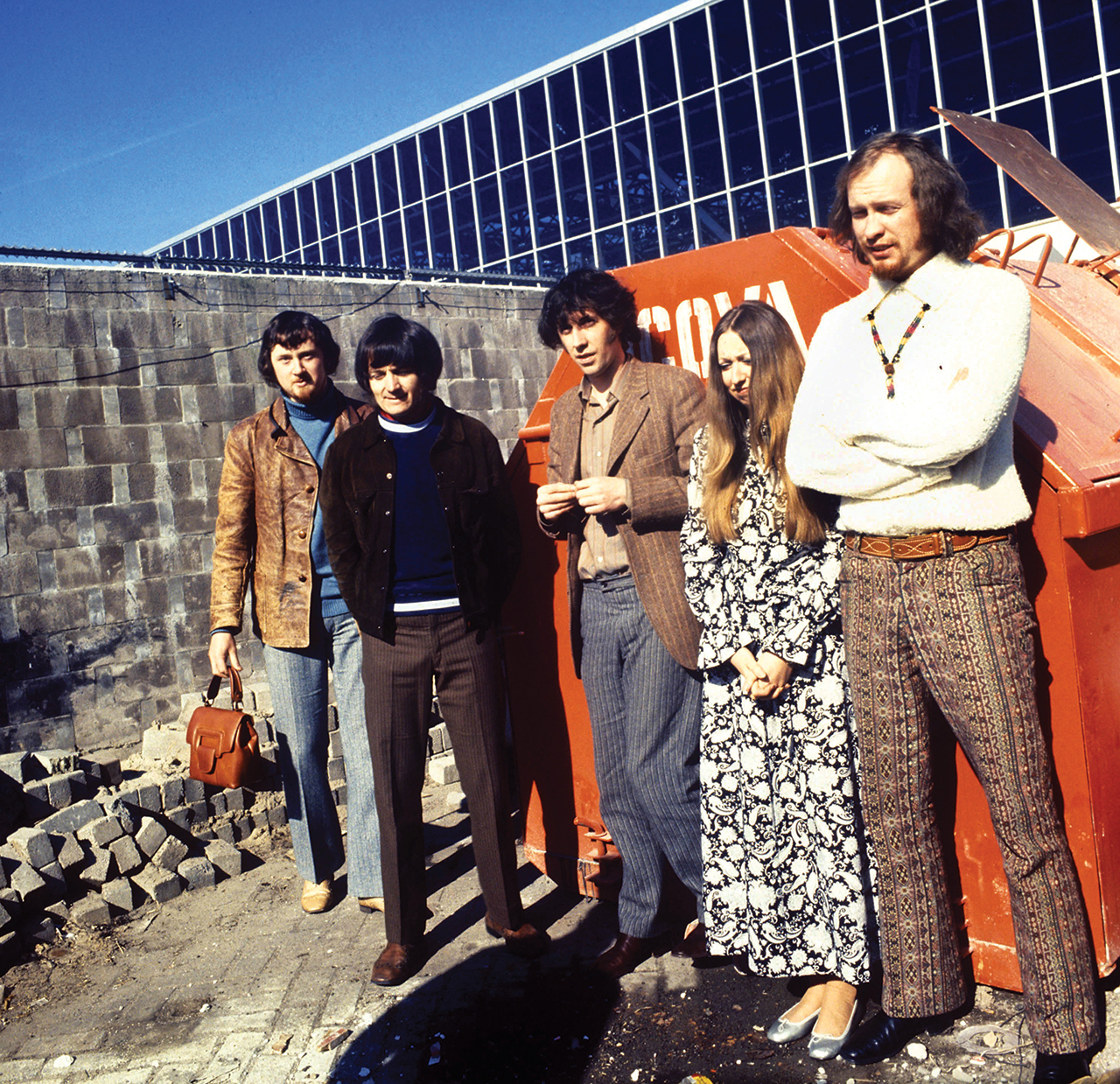

Pioneers from a time before labels like ‘progressive rock’ had assumed common coinage, Pentangle made music that really was impossible to categorise. A self-consciously arty hybrid of blues, folk, jazz, classical and something unnameable that could only be produced when the five individuals in the group stood – or, more usually in their case, sat – in the same room together. “It was all down to chemistry,” agrees Pentangle singer Jacqui McShee, 40 years on since they released their most famous album, Basket Of Light.

These days Pentangle tend to get lumped in with the folk-rock of the late-60s, and certainly the roots of the group’s main creative voices – McShee and guitarists Bert Jansch and John Renbourn – lay in the then-thriving UK folk scene. But as Jacqui points out: “We all had much broader musical backgrounds. Although I brought most of the traditional songs into the band, I didn’t actually own any folk records! I was into jazz, Miles Davis, John Coltrane. It was about experimentation. We all had an equal say in every song, jamming along, working on each tune together. Nobody was told how to play or sing; you just did what you liked.”

Although Jansch and Renbourn were familiar faces on the folk circuit, with several highly-regarded if uncommercial solo albums between them – including Bert And John, recorded during their time sharing a flat together in London’s St John’s Wood – the almost instant success that Pentangle achieved could not have been foreseen when its principle members first came together, playing for free at the Horseshoe Hotel in Tottenham Court Road in the spring of 1967 (recently demolished, the hotel was situated next to the Dominion Theatre).

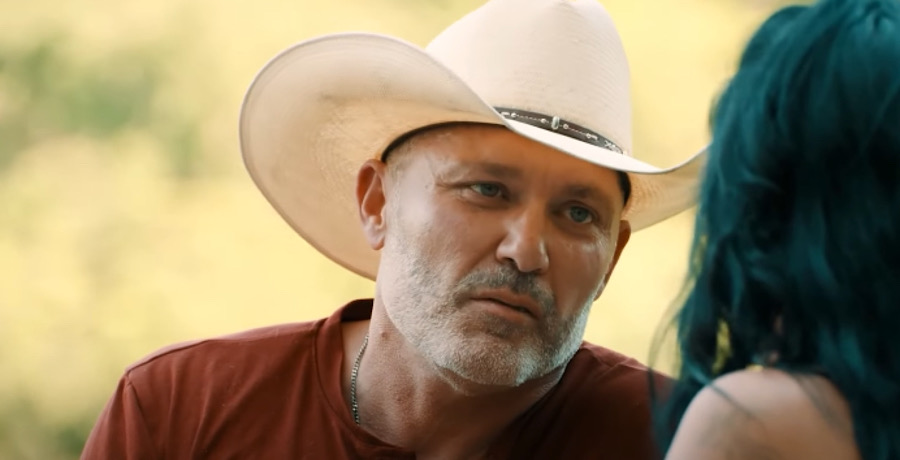

Memorably once described as “a man who seems in silhouette even in daylight”, Jansch was a disciple of fellow Scot, Davey Graham, whose modal tunings, learned on travels to Morocco, would also influence Jimmy Page, a man “absolutely obsessed with Bert Jansch” in the mid-60s. Described by Neil Young as “the Jimi Hendrix of the acoustic guitar,” Jansch took folk and added baroque, jazz, blues and rock. “I used to get thrown out of folk clubs for not singing the right songs,” he told me in 2006. “I was too influenced by all the non-folk music.”

Renbourn was more traditionalist, though no less experimental, looking beyond folk to medieval and early classical music for his inspiration, taking the acoustic guitar to inscrutable new heights as he weaved in and around Jansch’s enigmatic improvisations. As Jacqui says, “Nobody plays like Bert and nobody plays like John; put them together and it shouldn’t work but it just does. Sitting with them while they play, it always makes me smile, it’s so… hypnotic.”

The other pieces of the musical jigsaw, drummer Terry Cox and double-bassist Danny Thompson were equally catholic in their musical influences; both shared a love of improvisational jazz, had been part of Alexis Korner’s blues band, and jammed with future Mahavishnu Orchestra leader John McLaughlin. Thompson was also a larger than life character who liked to party.

“We were all drinkers,” Jacqui recalls with a laugh. “Going to New York for the first time, we were outrageously drunk all the way over on the plane, arrived at the hotel and it was all expenses paid by Warner Brothers. We were like kids in a sweet shop.”

Given the arty, free-flowing nature of the music and the era it was made in, one wonders if there was more to Pentangle’s offstage mien than mere drinking? More laughter. “There was some dope smoking and stuff, but nothing… drastic. As a kid I’d be sat in the pub with a brown ale hoping no one would ask me my age.”

Jacqui, who had sung with John and Bert at London folk haunts like Les Cousins, had also appeared on the former’s Another Monday album. When Thompson and Cox began joining in at the Horseshoe, “it just seemed natural.” It was the quietly-spoken but fiercely determined Jansch that suggested they make a permanent alliance. Pentangle’s name came from Sir Gawain’s shield in the Middle English poem Sir Gawain And The Green Knight, and represented the five members (points) of the line-up. “That came from John,” says Jacqui, “who knew about that sort of thing.”

The idea of becoming rock stars had never entered their minds, though. As Bert told me, “I was never interested in being famous, never interested in anyone else who was.”

Enter legendary managerial Svengali, Joe Lustig. “Joe had big plans for us,” Jacqui sighs, “which definitely worked for a while.” They certainly did. Launching the band with a showcase concert at the Royal Festival Hall, Pentangle found themselves “starting at the top and working our way down again,” as Jansch only half-jokingly put it to me.

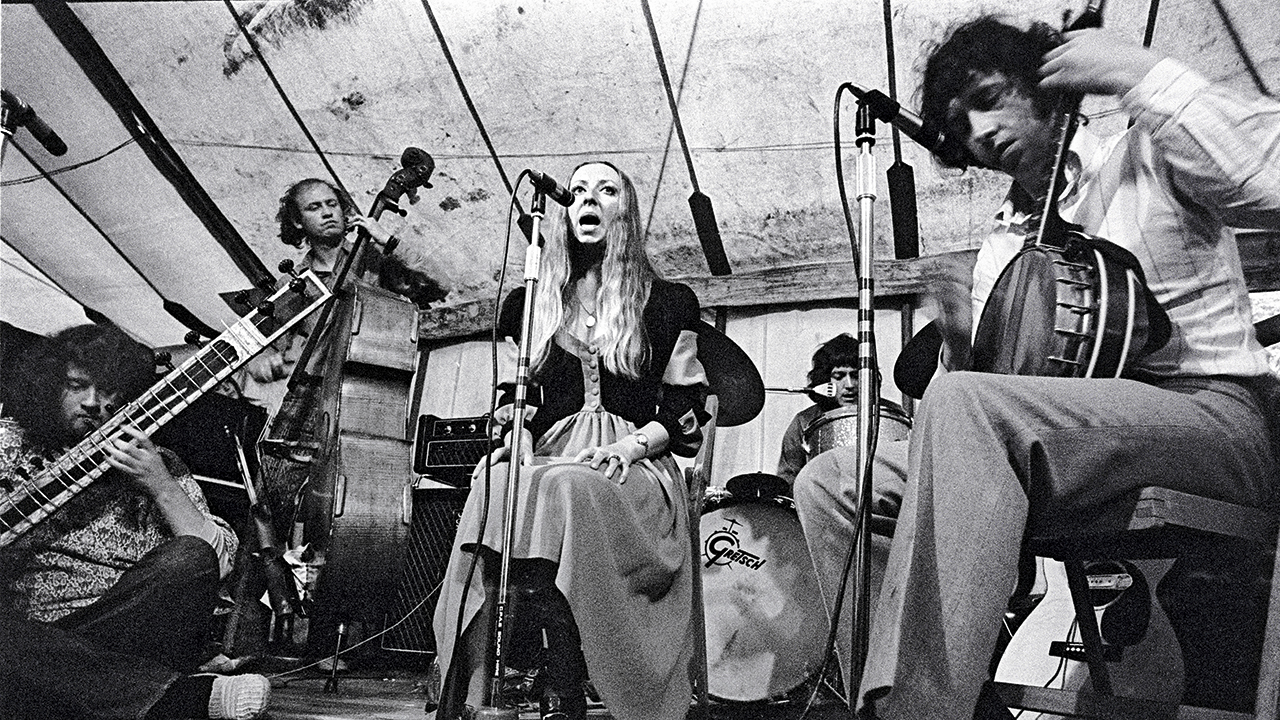

By the time Basket Of Light, their third album, reached Number 5 in January 1970, Pentangle were TV and radio regulars. The album even yielded a minor hit single with Light Flight, an earlier version of which had been the theme to the TV series Take Three Girls (the BBC’s first drama series to be broadcast in colour). How a piece of music that switched between 5/8, 7/8 and 6/4 time signatures became a chart hit remains a mystery – even to Jacqui.

“We were really shocked at having a hit record. Joe said it would have been a much bigger hit if we had expanded on [the subject matter of the TV show] but I stamped my little foot and said no, because it wasn’t really Pentangle style. Joe got a bit cross about it. But none of the rest of the band were bothered.”

Basket Of Light was not only their biggest hit but Pentangle’s most cohesive musical statement: a beguiling blend of traditional Olde English songs given fresh stylings – such as Once I Had A Sweetheart which Renbourn added a sitar solo to – and originals credited to all five members like Train Song, ostensibly a blues the band added endless sumptuous layers to, evoking the rhythms of a train, before melting into a dream-like middle section where Jacqui’s voice becomes a fifth instrument, giving the album its title in the line, ‘Love is a basket of light; grasp it so tight…’

“The previous album, Sweet Child, had been a double, half live, half studio stuff, but only because we didn’t have enough stuff to fill it,” Jacqui admits. “Basket… was the album that really summed up what we did.”

Produced by Shel Talmy, until then best known for his work with The Who, it was also the album that introduced the band to the rock-buying crowd, audiences bowled over by its seemingly bizarre mixture of heady originals like Hunting Song – based on the mediaeval story of a magic drinking horn sent to the court of King Arthur by Morgana le Fay – and inspired covers like Sally Go Round The Roses, a 1963 pop hit for early girl group The Jaynetts.

Jacqui: “I remember the studio was a big room with a clanky old lift. We would try things out but I was terrified of Shel because he was blind. One time were doing four-part harmonies, all standing around one mic, and Shel came up and said to us, ‘You’ve gotta be kidding’. We’d never had a producer before…”

The band became even bigger over in the US, regarded in the same light as other groundbreaking UK acts of the era like Cream and Led Zeppelin. “We would be advertised as this big rock group, which we weren’t. But we would play ever so loud and it would go down really well.” A shy person, McShee could “hide behind these other four big egos, which suited me down to the ground.”

At their debut, at New York’s Fillmore East, “the dressing room was several floors above the stage but the floor would thump up and down with the noise.” Sandwiched between the Sir Douglas Quintet and Canned Heat, they only survived, says Jacqui, because “Bill Graham came out and said, ‘Right you lot, this is a group from England and they play acoustic guitars so listen!’ And they did.”

Playing four nights at the Fillmore West in San Francisco with the Grateful Dead

was “slightly different because everybody was so stoned. We went quite smart but came back as hippies. Suddenly John’s got the dust-bowl jacket on and Terry’s got the fringe-jacket.” When Jerry Garcia later credited them with inspiring the Dead to adopt a more acoustic approach, “I thought, how could you remember? Because they were pretty off their faces at the time.”

Not that the rest of Pentangle was immune to such ideas. Bert admitted that he too began to live the rock star life – “drinking way too much, smoking more than ever.” In America, there was also cocaine. “Not a good drug,” he told me with a hangdog expression.

In the wake of Basket…’s success, by 1970 Pentangle had appeared at the Isle of Wight festival, headlined Carnegie Hall, and recorded a soundtrack for the film Tam Lin. But their next album, Cruel Sister, released in October 1970, was not a hit. A collection of traditional material given ambitious progressive twists like the 20-minute-plus version of Jack Orion, Jacqui now admits now the group was “running out of steam.”

The writing was on the wall and within three years Pentangle, who never had another hit album, was no more. “The last full year we were together we went to the States three times, we went to Australia; we went to parts of Europe. There was no time to record. Joe would have us on the road constantly and we just got tetchy with each other. We weren’t working on new stuff and Bert wanted to do more on his own anyway. You start to think: I can’t stand it anymore.”

Fortunately, the story of Pentangle didn’t quite end there. When they reunited to receive a Lifetime Achievement award at the 2007 BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards, it was as if they’d never been away – a fact brought home when Terry Cox fluffed his way through Bruton Town.

“Keep going, I thought,” laughs Jacqui, “people will just think we’re trying out something new…”

This article originally appeared in issue 5 of Prog Magazine.