Saying “fuck it” can be pretty liberating. Though the era of widespread dancehalls and discotheques is behind us, the ethos that was born and grew in those buildings still has a place in the world of today. House music is making a much-needed comeback, and Feral Girl Summer is riding shotgun. For the next few months, we’re abandoning morning routines, attuning ourselves to the celestial rat and, most importantly, outlasting the waves of societal dread that threaten to set in.

The closest thing disco got to an official date of death was July 12, 1979. A disgruntled Steve Dahl held an event called “Disco Demolition Night” at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. Dance music haters flocked to the baseball stadium, offering Donna Summer, Sister Sledge and Bee Gees albums as tribute; Dahl’s promise to blow up the records was that night’s main attraction. Tens of thousands of people across Illinois arrived at the park longing to contribute to and witness the eruption of shattered, molten vinyl across the green of Comiskey Park. Depending on who you ask, this wasn’t just about the music: Disco had become a liberating force for Black, Puerto Rican and gay people throughout the United States. Surely the odd Aretha Franklin and Billy Henderson albums that got mixed in with the disco slated for destruction weren’t spared from the conflagration. After the stadium had reached its capacity of 50,000 attendants, about 20,000 were still left outside, but it wouldn’t be long before they forced their way in and onto the field. The resulting riot ended in destroyed batting cages, impromptu bonfires and 39 disorderly conduct charges.

Read more: A24’s The Idol trailer is unhinged Hollywood excess

Even still, disco hadn’t really died. It was silly to think it had in the first place. Disco was tenacity made manifest by sound. The genre was born among the worst economic conditions America had seen since the Great Depression, and dancing at the club was just as much an act of collective perseverance as it was an exercise in staying on beat. No, instead of fading away, the genre’s stalwart lovers retreated into a period of isolationism.

In Chicago, invite-only clubs kept the spirit of dance music alive after it was chewed up and spit out by mainstream America. The racial and sexual minorities who found empowerment through disco also came to imbue house music culture with that same sense of radical acceptance by frequenting these venues. There, an army of DJs stood at the ready to spin disco’s greatest hits, and when that got stale, they started remixing.

DJs were sonic surgeons, snatching pieces of one song, grafting them to another and using synthesized drums to stitch the two together. House was the result of their work. In the dead of night, they revealed their new creations to rabid audiences. Tight loops of dusky 808s gave way to sunrise-colored synths, and clubbers danced enraptured by the beats and whatever drugs they may have consumed earlier in the day.

Read more: Balenciaga said it’s time to listen to music in style

House music is pure satisfaction diluted from the distraction that its predecessor, disco, promised. It reaches out to listeners with rhythms that stir their heartbeats into a frenzy and synapse incinerating samples. It says, “You are here, now, in this moment, and nowhere else. Doesn’t that feel absolutely perfect?”

Nearly half a century since the genre’s inception, there still exists a great need for its centering power. The early 1980s were marked by an all too familiar disillusionment with the American state and its inflated economy. Similarly, today Americans face a mounting disappointment with governmental processes and the elevated price of goods. As the problems of the 21st century increasingly morph to resemble those of the ’80s, it only makes sense that culture would also begin to employ the coping mechanisms that proved effective in years past.

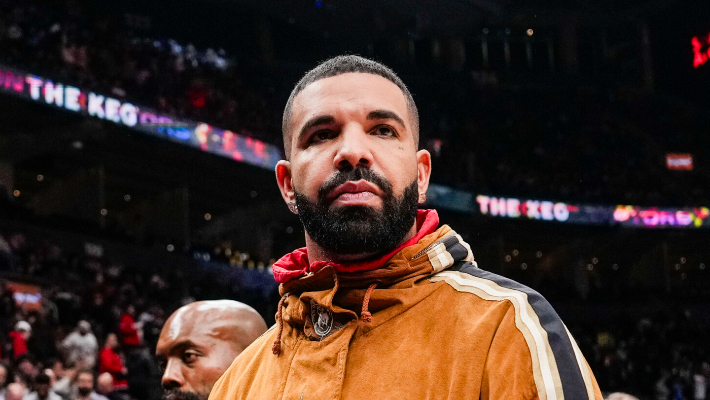

In an era where it seems the only product to resist price hikes is Arizona Iced Tea and the American government elevates its constant flirting with blatant oppression to full-on relationship status, house is attempting to balance the psychic scales. Beyoncé’s “BREAK MY SOUL” is steeped in the elements that characterize house music not only musically but also lyrically. The track is littered with synth percussion hits and claps that confer to listeners as much their unconquerable swagger as they care to accept. Social media is awash with the positive effects of the track. Videos of babies nodding their heads to the track are snuggled close in the timeline to clips of retirement homes using the song for aerobics classes. “You won’t break my soul” has become a rallying cry against the erosive forces of daily life. Even Drake’s often dour and childish musings on relationships can’t help but take on a more optimistic, accepting tone when set against the throbbing bass characteristic of the genre and bitter displays of post-breakup glow-ups become an invitation for reconciliation.

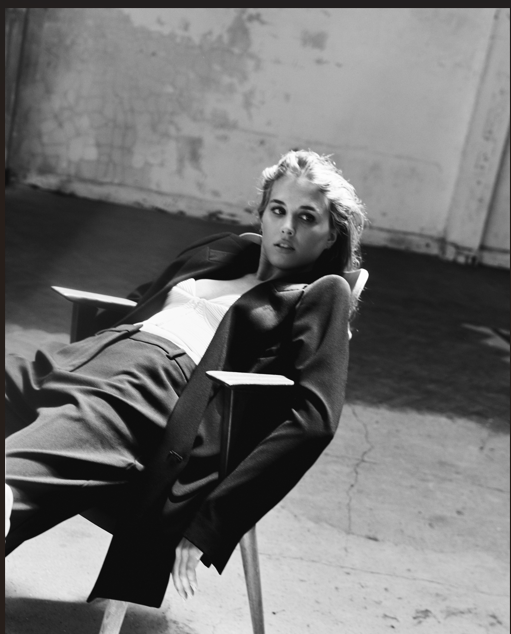

The TikTok and Twitter trend rising alongside this mini house revival also fulfills this cultural need for triumph and release. Feral Girl Summer, of course, owes its creation to 2019’s Hot Girl Summer. After three extremely long years, the Megan Thee Stallion-inspired meme has been transfigured into one less concerned with appearance and more with unhinged behavior. The thing is, sometimes Feral Girl Summer isn’t all that feral. It can be; to some people, it’s slashing tires and weeklong benders. To others, it’s accepting cellulite and not bothering with doing their hair and makeup every time they leave the house. Either way, this abstraction from glitz and glamour to fang and claw betrays the meme’s deeper principles. The best answer for all of the everything that’s been going on recently remains practicing self-acceptance with a dash of reckless fun. Dance on some tables, have some raw pasta as a snack or maybe just look in a mirror and think “I love you.” It’s been a rough few years. You owe it to yourself.

![[VIDEO] ‘The White Lotus’ Season 2 Trailer, Release Date on HBO Max [VIDEO] ‘The White Lotus’ Season 2 Trailer, Release Date on HBO Max](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/white_lotus_season_2_first_look_3.jpg?w=620)